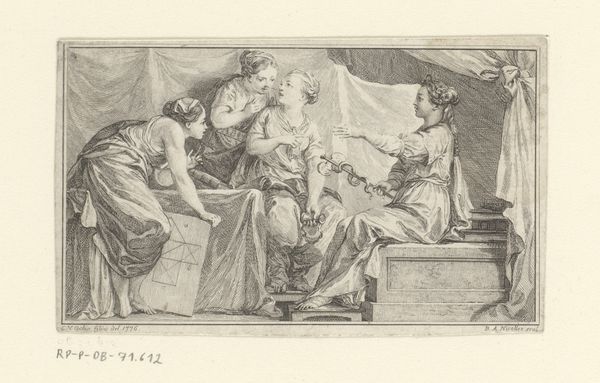

drawing, engraving

portrait

drawing

baroque

figuration

pencil drawing

portrait drawing

history-painting

engraving

Dimensions: height 376 mm, width 435 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have "Angelica en Medoro", an engraving created around 1754 by Antoine Radigues. The crisp lines of the figures against the softer background are immediately striking, aren't they? Editor: Yes, it’s beautiful, though almost unsettling. There's a strange tension in their faces, and the woman’s gaze feels particularly forward for the era, even defiant. The intimacy and vulnerability presented feels almost staged for an audience that will probably not accept her agency as portrayed here. Curator: The medium allows for fine detail; look at the texture Radigues achieves in the drapery and hair. This speaks to the artisanal skills that were prized by engravers during the Baroque era and their meticulous crafting skills. Think about the workshops and the hours of labor involved in creating the copper plates for printing. The engraving also served as a reproductive medium, expanding its audience and potentially generating wealth for both the creator, publishers, and associated merchants, contributing to an active, growing, creative industry during its time. Editor: Indeed, but look closer: Angelica is depicted with Medoro inscribing their love into the landscape. Their intertwined hands represent perhaps not only romance but maybe a shared power in declaring one’s love publicly. What would this declaration mean during its historical setting, during the 18th century when women often occupied secondary status, without societal, and financial freedoms we consider baseline? The deliberate mark-making upon that architectural facade carries immense subversive power. Curator: A key point; consider, too, the accessibility of engravings compared to painting. This love story, reproduced multiple times, spreads amongst varied social classes through an expanding marketplace for imagery, altering our experience and access of what "art" is allowed to be. This shift democratizes access to subject matter traditionally reserved for wealthier patrons and transforms modes for both distribution and access for art that lasts long after an aristocrat’s commission. Editor: I also observe her slightly plunging neckline–a visual shorthand for her sexual liberation. This isn't merely a romantic image; it's a revolutionary statement about autonomy during an age where feminine virtues were valued under much more restrained conditions. Considering broader issues involving social identity here helps expose the nuanced and revolutionary ways Radigues addresses constraints experienced by females within artistic confines from back in those days, thus making it into a subtle narrative, one worth more contemporary, feminist appreciation! Curator: It prompts reflection how technological capabilities could change our interaction with images throughout all of these eras of production. Editor: Right; hopefully our brief conversation gives visitors plenty to consider moving forward, no?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.