Dimensions: image: 14.5 x 9.9 cm (5 11/16 x 3 7/8 in.) page size: 21.6 x 13.5 cm (8 1/2 x 5 5/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

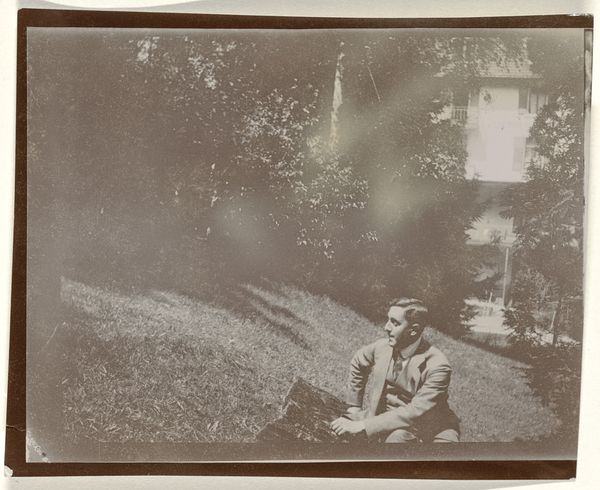

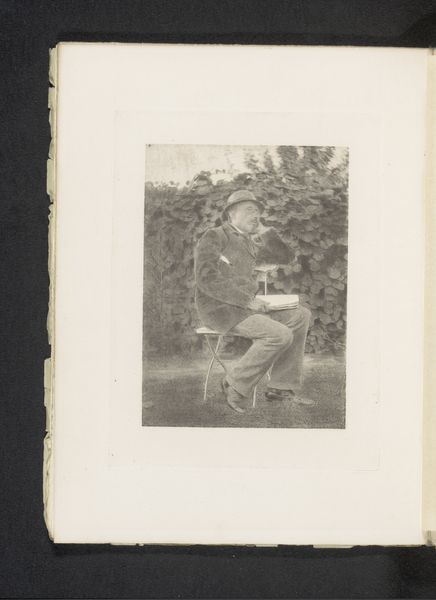

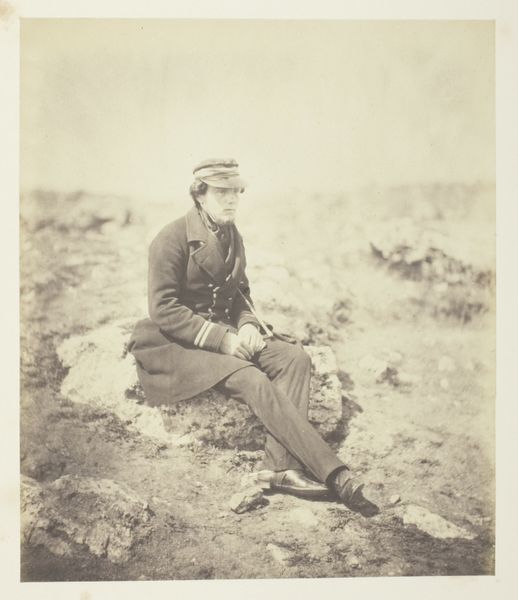

Curator: Alfred Stieglitz's gelatin silver print, titled "Bavaria", dating to 1886, is a poignant image. What's your initial take on it? Editor: There's an overwhelming sense of weary finality in this composition. A man rests amidst grave markers—perhaps a laborer overcome by the burdens of his life, his pose mirroring the solemnity of his surroundings. Curator: It resonates with romanticism's fascination with mortality, doesn't it? The man's closed eyes—a universal symbol of sleep but also suggestive of passing. And those crosses; can you expand on their deeper context and symbolism? Editor: Absolutely. The cross marks not just death, but faith. But beyond any theological interpretations, here the image could function as social commentary: that for the working class, the promises of faith ultimately resolve into unending toil, broken dreams, a premature rest on earth. Curator: Considering the photographic methods that existed at the time, I think there may be room for some understanding of cultural context as well. There are elements of 19th-century genre painting here. Given that the artist gave the title Bavaria, the question remains: Was Stieglitz pointing at this location to illustrate a sentiment, emotion or fact about its own time? Editor: Absolutely; the romantic undertones you pointed out, that were influencing the art in Stieglitz’s era cannot be excluded. We should note that Stieglitz's choices here can certainly prompt a conversation about what Romanticism idealized, and perhaps even distorted about, rural life. Curator: Indeed. The light, almost hazy, also enhances that romantic feel. It doesn’t capture reality so much as translate it. We see with our eyes a certain mood that he clearly intends the image to have. Editor: I agree. It invites us to meditate on class disparity and its intersectionality to existential concepts, don’t you agree? Stieglitz presents, intentionally or otherwise, an exploration into rest and resistance, of sorrow and survival. Curator: Indeed. The power of symbols lies in their ability to accumulate different interpretations over time. In conclusion, the work shows not just a person in a region but brings complex dimensions into a very complex situation. Editor: I’d just add to what we discussed about symbolism to note that images that seek to freeze historical contexts allow us to ponder historical disparities that still reverberate, pushing us to critically re-examine our society today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.