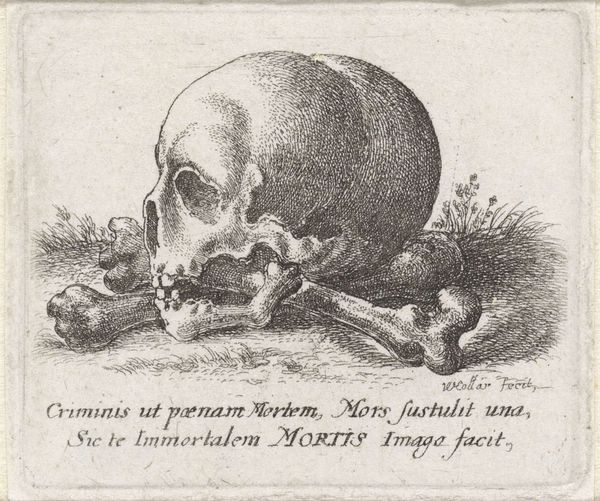

print, oil-paint, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

form

#

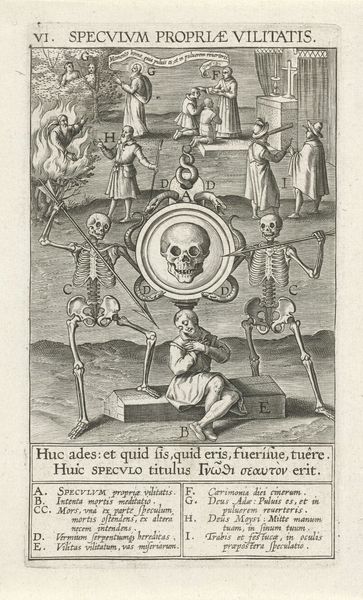

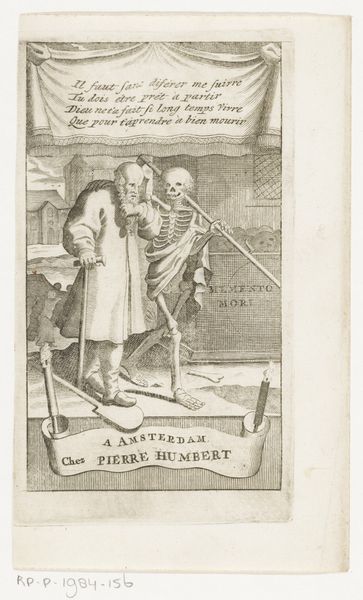

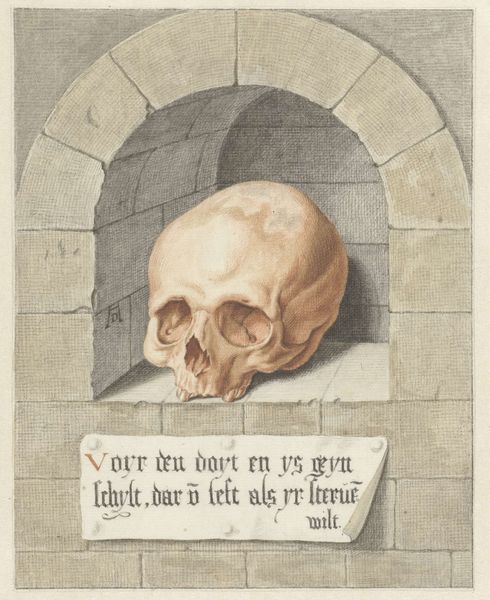

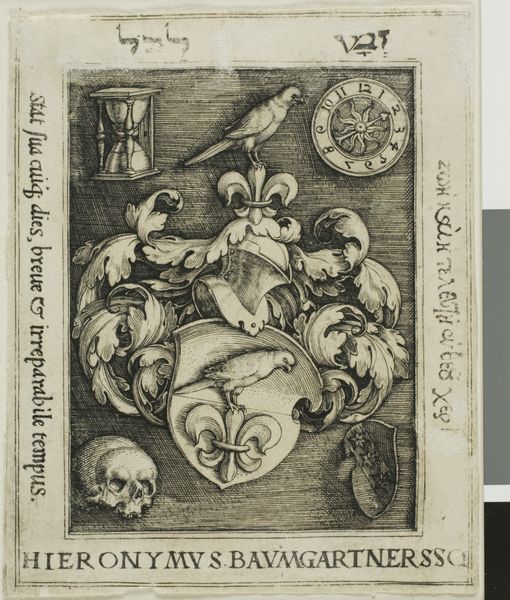

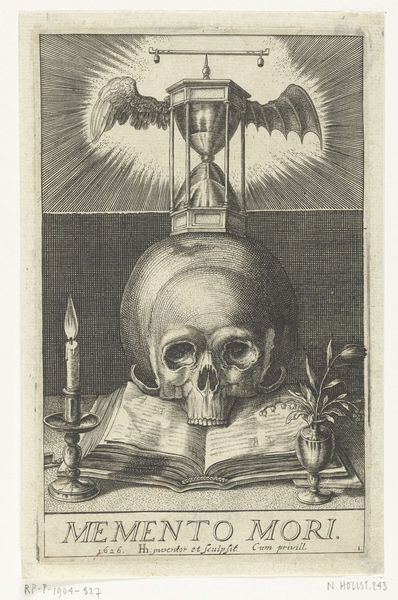

vanitas

#

momento-mori

#

abstraction

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 98 mm, width 75 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: At first glance, it has the chilling effect of the black plague memorials, that same memento mori aesthetic that urges one to remember the transient nature of existence. Editor: That’s definitely the mood. Looking at Johann Sadeler I's "Vanitasvoorstelling met een schedel en twee beenderen" – a work from sometime between 1560 and 1620, currently housed at the Rijksmuseum – it's easy to get that impression. But tell me, beyond the gut reaction, what catches your eye, symbolically speaking? Curator: Well, right away the skull speaks of death, the ultimate end. Beneath it, we have crossed bones in an X that reifies a warning—hazard, caution, toxicity, as with its adoption into warning labels in industrial applications, yet within its original art form it is presented with more delicacy than starkness. There are slight differences, such as the plants and hill where the remains reside. The image also presents an inscription that continues these motifs into the work. It feels as if the composition is attempting to warn without creating deep disturbance, though this is a balancing act given the inherent theme of the piece. Editor: The interesting thing for me is the technique: it's an engraving. Consider the labor involved, the precise and repetitive actions required to carve those lines into a plate, wiping the ink, the printing itself, how these prints could circulate. Curator: Indeed, this mode of creating and distributing images amplifies the meaning. As a widely reproducible image, it is a symbol circulated en masse that would carry and preserve cultural beliefs and concerns across communities, a visual artifact of shared psychological experience with life and death. Editor: And that dissemination impacts our reading. Instead of singular veneration like a painting, the materiality of the print makes it more like folk art, almost a repeatable charm to ward off evil and give recognition. There’s something powerful in the potential for an artwork like this to have entered daily life in the 16th and 17th centuries. Curator: It does, doesn’t it? I can appreciate that. All those hands it must have passed through. In the end, though, I think it keeps pointing us back to our own mortality, doesn't it? Editor: Absolutely. Its inherent value, both emotional and literal, lives on.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.