Dimensions: support: 1283 x 800 mm

Copyright: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

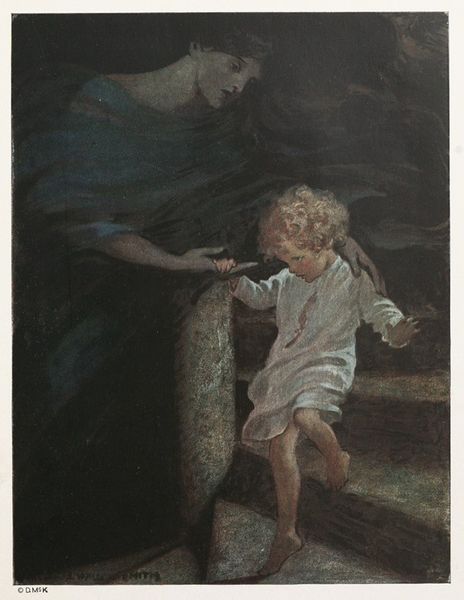

Editor: This is George Frederic Watts' "Death Crowning Innocence." I find the tenderness in this work so moving, but also unsettling. What do you see in this piece? Curator: This work visualizes complex Victorian anxieties about mortality and childhood. Consider the era's high infant mortality rate, and how that might shape perceptions of innocence and death. How does Watts perhaps challenge or reinforce societal views on these issues? Editor: I hadn’t considered the historical context of infant mortality. The painting takes on a new layer of meaning, almost like a social commentary. Curator: Exactly. Watts uses symbolism to explore how society grapples with loss and innocence. Reflecting on the sociopolitical dimensions within art enhances our understanding. Editor: Thank you. It’s fascinating to consider the intersection of art and social issues. Curator: Indeed. Art is never created in a vacuum.

Comments

tate 10 months ago

⋮

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/watts-death-crowning-innocence-n01635

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 10 months ago

⋮

Death Crowning Innocence was among those works that Watts presented to the Nation in 1897 and which are now held in the Tate collection. Mary Watts recalled how on hearing the news of the painting's success at the New Gallery in 1888, Watts, who had originally intended to sell the picture, 'settled at once that it was to be of the number offered to the nation' (Watts, II, p.123). The painting was referred to as 'The Angel of Death' by reviewers of the 1888 exhibition, among them the critic of the Art Journal, who felt that Watts's Death Crowning Innocence 'touches one in virtue of the poetry of idea rather than of the poetry of treatment or colour' (Art Journal, 1888, p.221). In Death Crowning Innocence, the 'Angel' holds a dead child to her bosom and encircles the infant with her great wings in a manner of tender protection. Hugh Macmillan described the face of the angel as 'full of pity' and with 'an expression of intense yearning', commenting also how in Death Crowning Innocence, 'all the lovely details stand out clearly from a background of the softest ethereal blue' (Macmillan, pp.246). The subject of this work was instigated by the sudden death of Mary Watts's young nephew, following a fall from a pony. Watts described his design for Death Crowning Innocence in a letter to Mary, enclosing also a sketch of it for the grieving mother: 'I am making a design which hereafter may be lovingly worked into a monument, The Angel of Death with a child in her lap on whose head she is placing a circlet, Death the Angel Crowning Innocence'. Mary replied: 'I long to see the angel and child … You are quite wrong in thinking that you are anything but a comforter, even to the most sorely stricken' (quoted in Chapman, p.122). Watts's portrayal of Death as a benign, angelic and moreover womanly figure, breaks with the traditional iconography of Death as a 'grim reaper' and can be seen in other works by him, such as The Court of Death (c.1870-1902) (Tate N01894). Here, Death, an enthroned and winged female figure, again holds a baby in her lap, and of this Watts explained that 'even the germ of life is in the lap of Death' (quoted in Watts, I, p.308). At a later date, Watts spoke of Death Crowning Innocence as 'the gentle nurse that puts the children to bed'. There is another, smaller known version of the composition which was painted after the exhibition of the Tate work in 1888, and which was shown at the Royal Academy in 1905. Further reading:M.S. Watts, George Frederick Watts: The Annals of An Artist's Life, London 1912, II, pp.59-60, p.123.Ronald Chapman, The Laurel and The Thorn: A Study of G.F. Watts, London 1945, p.122.Hugh Macmillan, G.F. Watts, London 1906, pp.246-8. Rebecca ViragMay 2001