Dimensions: image: 275 x 380 mm sheet: 365 x 460 mm

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

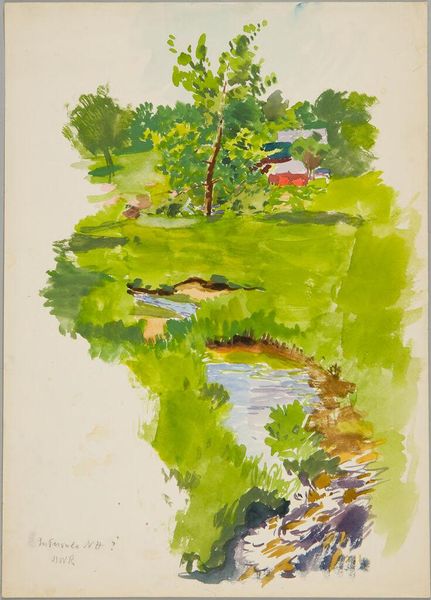

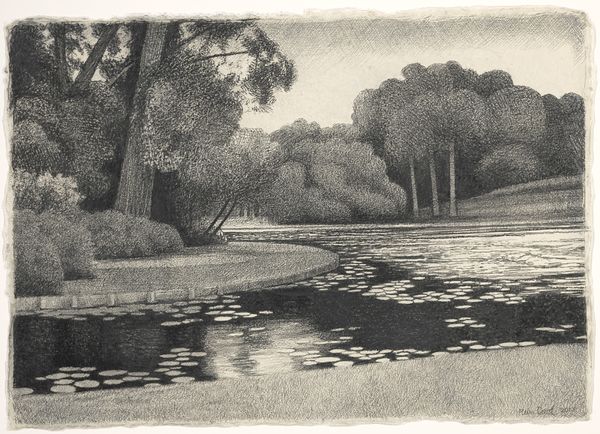

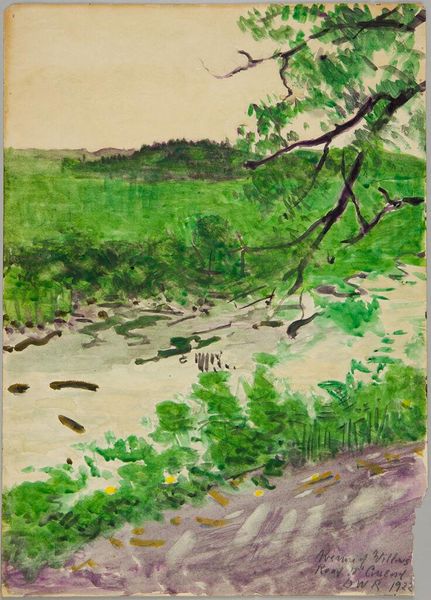

Curator: It’s wonderfully serene, isn’t it? Such restful harmony. Editor: Restful until you consider who benefits from all that leisure, who exactly *gets* to lie around by a river. But, okay, let’s get to it. Curator: Fair enough. We're looking at Emil Ganso's "Summer (No. 1)", likely completed between 1933 and 1934. It seems to be a print, judging by the visible texture and the graphic clarity of the shapes. Ganso has managed to compress so much idyllic contentment into this deceptively simple scene. Editor: Agreed, it's simple, almost…too simple. It lacks depth. The perspective is wonky. It's sanitized, isn't it? The stream winds neatly through manicured grounds and the colors are all placid—pale blue sky, various light and mid-tone greens. This visual simplicity is very telling. Curator: Perhaps "simple" is not quite right—"distilled," maybe? There are powerful, recurring images in landscape art that resonate with the human psyche, such as the water that symbolizes flow and change, rebirth. In this piece the artist positions viewers as though they were also floating or dreaming. It might well represent how artists found retreat in natural beauty while they suffered through existential turmoil and fear during The Great Depression in the 30s. Editor: Well, for some of us. Landscape has never been innocent. Whose land is this? We see a neat little barn there and animals resting comfortably. "Summer (No. 1)" reflects not the general struggle, but perhaps Ganso's specific position, enjoying relative ease—likely supported by the booming art market between the two world wars. It also romanticizes the countryside in a way that conveniently omits any trace of rural labor or social struggle. The artist conveniently eliminates the complicated social landscape of the 1930s. Curator: You see an exclusion—I see the exclusion of conflict as the point. These symbolic depictions of idealic nature remind the artist and his contemporary viewers of times before wars, displacement, and oppression, or, maybe more precisely, provide a temporary escape from these real-world horrors. Editor: Hmm. While I appreciate the search for universal symbols and shared experiences of psychological respite during the hardships, I’m wary of excusing the painting's naiveté. It strikes me as more an example of unconscious biases being visually manifested through symbolic exclusion. Curator: Perhaps, but even such biases hold important historical value. By studying them, we may decode where we have come from, and imagine pathways toward an improved future. Editor: Right, by challenging such images and their subtle encoding of ideology. Curator: Exactly!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.