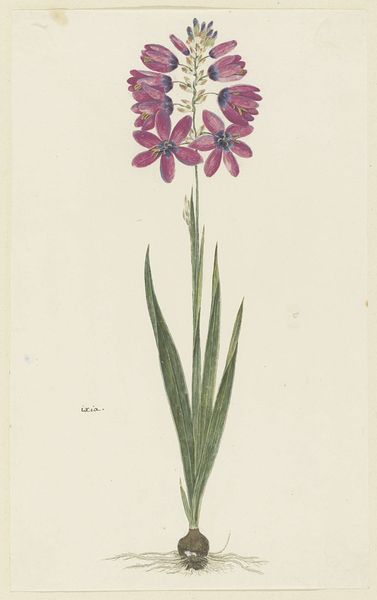

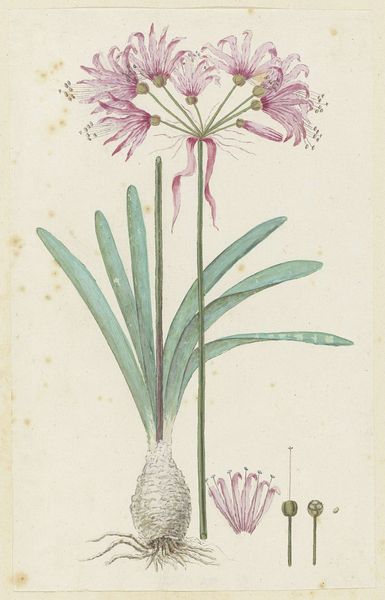

Hessea cinnamomea (L'Hérit.) Durand & Schinz. (umbrella lily) Possibly 1777 - 1786

0:00

0:00

drawing, coloured-pencil, watercolor

#

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

#

water colours

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

watercolour illustration

Dimensions: height 660 mm, width 480 mm, height 389 mm, width 267 mm, height mm, width mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Robert Jacob Gordon’s drawing, "Hessea cinnamomea (L'Hérit.) Durand & Schinz. (umbrella lily)", possibly from between 1777 and 1786. It appears to be rendered with watercolor and colored pencil, and I find the botanical details quite fascinating. What strikes you about this piece? Curator: Considering Gordon's position within the Dutch East India Company, this botanical illustration offers more than just scientific observation. The paper, pigments—where did they originate? How were they traded? The labor involved in their production, from mining to manufacturing, shaped this image as much as Gordon’s hand. Think about the social context intertwined within the very material of the artwork. Editor: That's interesting, I was only looking at the plant itself. So, the materials reveal something about global trade and colonial economies? Curator: Precisely. Watercolors and colored pencils were becoming increasingly accessible, fueling both scientific pursuits and artistic endeavors. Who had access to these materials, and who benefited from their distribution? Also consider that "umbrella lily" is an attributed title now -- what did indigenous populations call it? Were their uses of it documented by Gordon or other members of the company? These details inform the art object in crucial ways. Editor: I hadn’t considered that before. So, by examining the materials, their origins, and the means of production, we can uncover hidden layers of meaning related to labor and colonialism. Curator: Exactly. It compels us to question traditional hierarchies in art history, moving beyond the purely aesthetic to consider the social and economic forces that shaped the work. Editor: I've definitely learned a lot about looking at art with a materialist lens today! Curator: Me too. Thinking about how this botanical illustration became an instrument of colonialism and commerce gives me a new framework for understanding art objects!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.