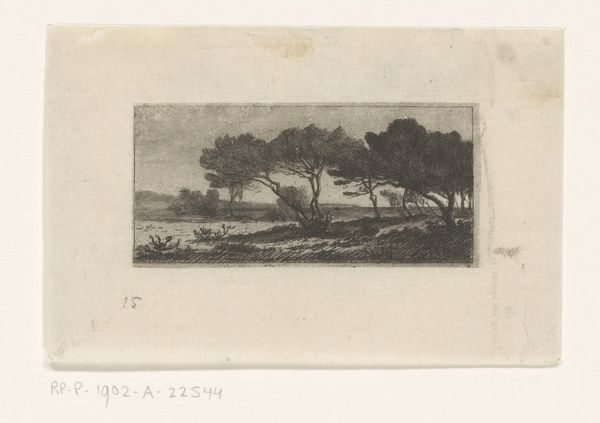

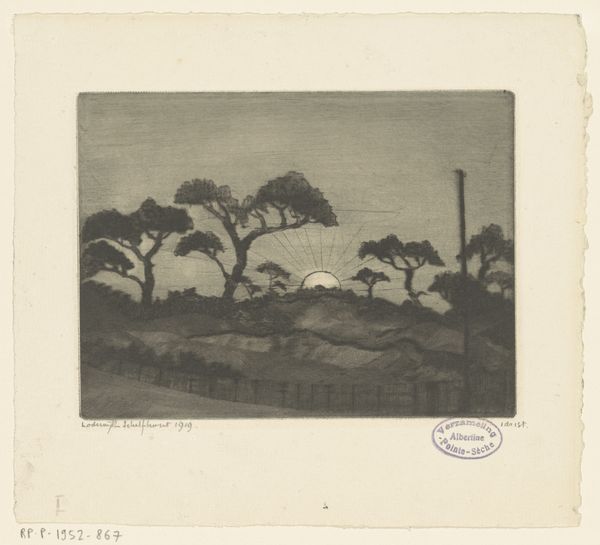

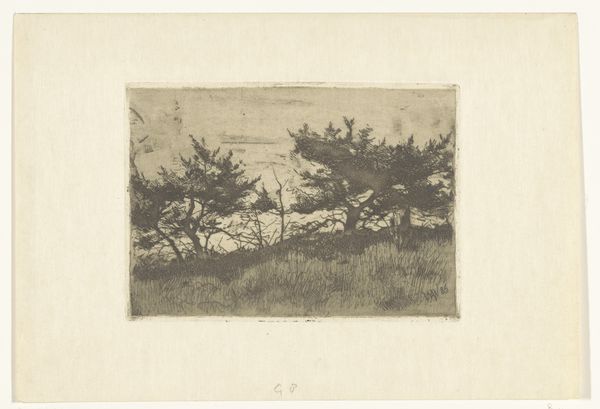

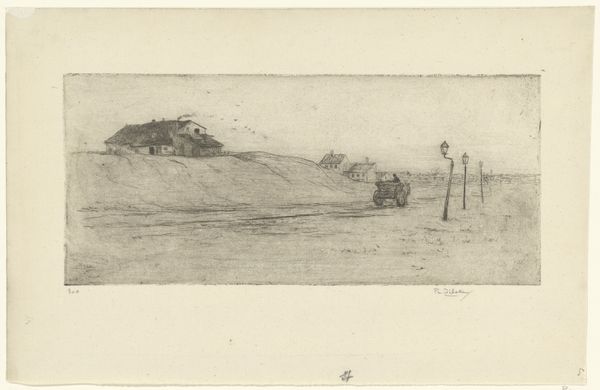

Zeegezicht met duinen op Porquerolles 1851 - 1910

print, etching

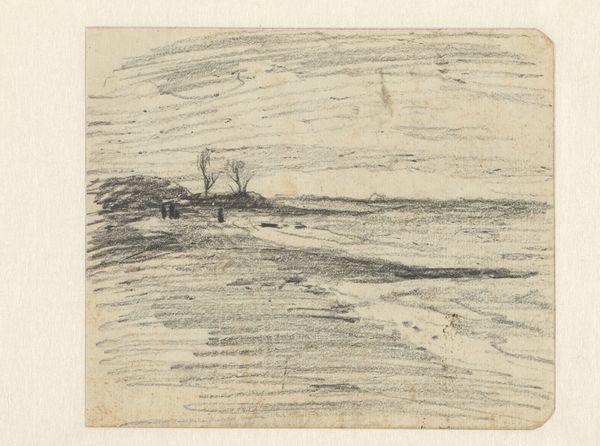

pencil drawn

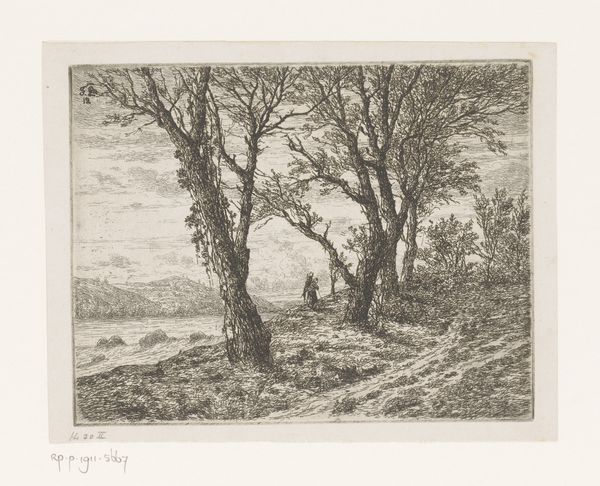

impressionism

etching

landscape

Dimensions height 42 mm, width 80 mm

Curator: Before us, we see “Seascape with Dunes at Porquerolles," a work attributed to Carel Nicolaas Storm van 's-Gravesande, created sometime between 1851 and 1910. It's currently held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: The subdued tonality immediately strikes me; it's a quiet scene. The etching has a soft, almost dreamy quality, even though the lines are quite precise when you look closely. There is this clear contrast between the textured dunes in the foreground and the flat surface of the water, divided by only two trees that grow on the coast line. Curator: I am interested in the location chosen. Porquerolles has historically been an important strategic and ecological site, but here it is treated as pure landscape. Knowing this work was produced during a period of significant industrial expansion and burgeoning colonial power, what do you see in this representation of a relatively untouched seascape? Editor: I see an attempt to capture a space relatively untouched by the massive consumption of resources back home, but still fully relying on them for its material support: the ink, paper, the press involved, etc. It prompts reflection on labor of creation and consumption—consider the extraction of materials needed for printmaking in the context of a globalizing economy. It speaks to the labor involved in rendering the sublime. Curator: That's a fascinating point. By focusing on a location seemingly outside the grasp of industrialism, it presents a romanticized vision, one that obscures the relationship between the art object and the infrastructures which allowed it to be produced. But I also think about who has the time and leisure to appreciate such untouched nature. Is it accessible to all, or mainly a bourgeois privilege? Editor: Precisely. The print is, in itself, a product of certain privilege – its value predicated upon its presumed connection to an "unspoiled" natural space, accessible mainly to the elite. Curator: Looking at it through this lens certainly changes one's interpretation of the work. Instead of seeing a tranquil landscape, we see a quiet reflection of power dynamics embedded in material culture. Editor: Exactly. It forces us to acknowledge the often-unseen labor and extraction that supports even the seemingly most innocuous scenes. Curator: Indeed. It reveals how the pastoral ideal itself is enmeshed within complex networks of production, labor, and historical contingency. Editor: By situating it there, we gain a deeper understanding of what seemingly simple landscape represents.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.