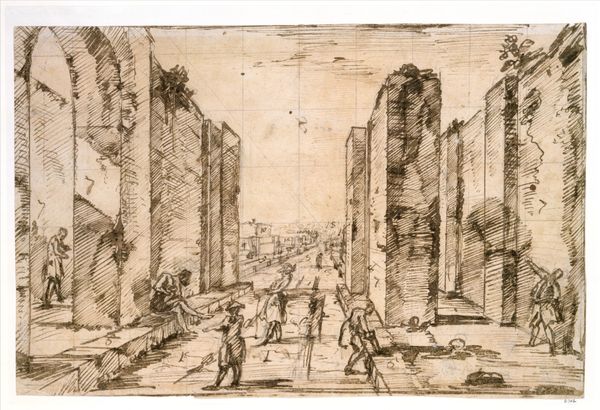

drawing, etching, ink

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

ink drawing

#

ink painting

#

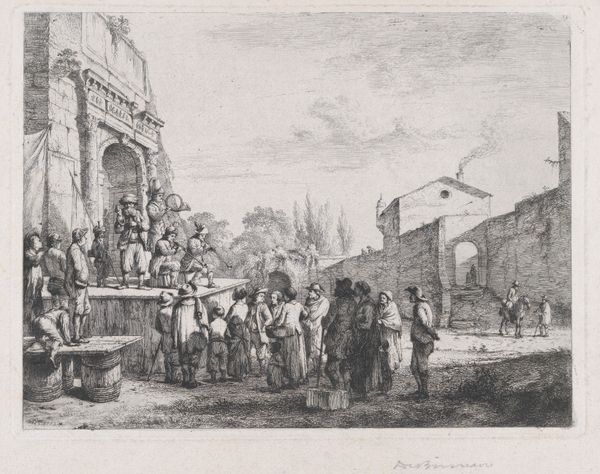

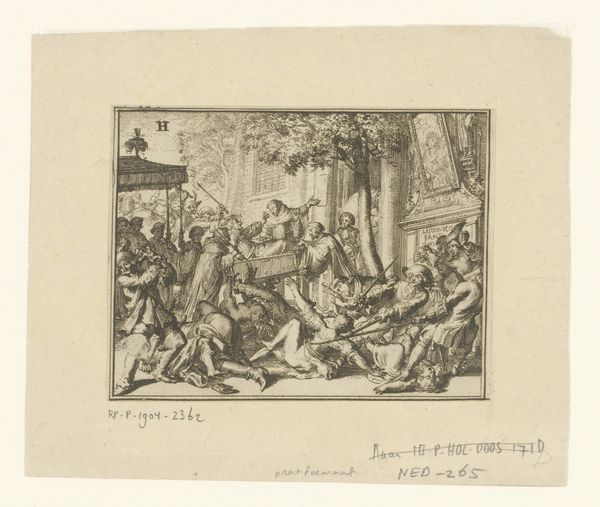

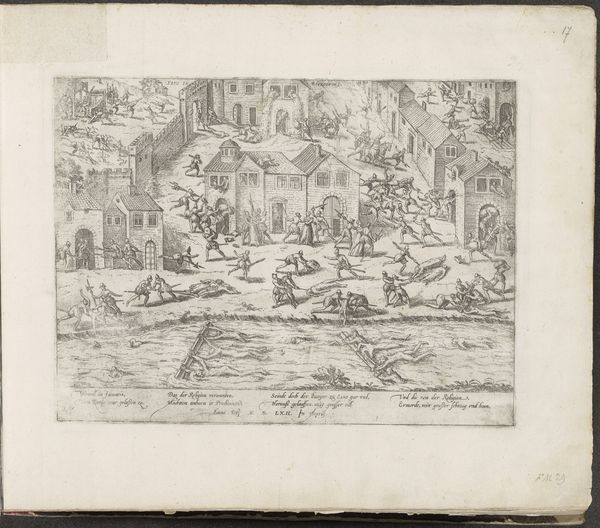

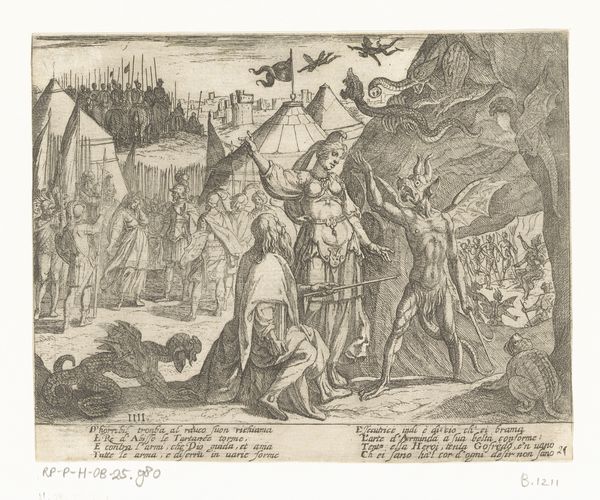

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

ink

#

ancient-mediterranean

Dimensions: 513 mm (height) x 777 mm (width) (bladmaal), 80.5 cm (height) x 112.3 cm (width) x 3 cm (depth) (brutto)

Curator: This is Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s etching from 1777, "The Tomb of the Istacidi, Pompeii," currently housed at the SMK, the National Gallery of Denmark. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It's stark, almost brutally so. The dense linework creates a scene of harsh sunlight and shadowed decay. It’s melancholic, but also feels immediate, as if capturing a moment in real time rather than an idealized vision of the past. Curator: Interesting. Let’s think about the processes involved in creating this scene. Piranesi was not only an artist, but an etcher and printer too. We’re looking at lines etched into a copper plate, inked, and then pressed onto paper. The texture and the contrast between light and dark, which you’ve astutely picked up on, are integral to the process of printmaking, but also tell a story about the manual labor involved in creating the image. Editor: Absolutely. The emphasis on materiality here – from the ancient ruins depicted to the very ink on the page – also speaks to power dynamics. Consider how this piece recontextualizes Roman history. Piranesi lived in a Rome colonized by powerful families, and by foreign wealth on the Grand Tour. How does he participate in or resist those power structures in representing the ruins and this moment of excavation? Curator: I would add that this etching isn’t just documentation; it’s almost speculative archaeology. We see the remains of a tomb, but also figures actively unearthing and interpreting it, reshaping it for contemporary audiences. Editor: Precisely. It prompts questions about labor too. Note the figures within the scene itself, what is the social context for those people? This labor provides visual, historical capital for the colonizing structure around the practice of archeology at the time. Who benefits from this discovery, and at what cost? Curator: Looking at it through a material lens reminds us that this image itself is an object with its own history of production and consumption, a commodity circulating within a specific economic and cultural system. Editor: Ultimately, Piranesi offers a critical gaze – he’s documenting, yes, but also provoking reflection on history, power, and representation itself. Curator: Agreed. And engaging with the art in that way brings a richer experience. Thanks!

Comments

statensmuseumforkunst about 2 years ago

⋮

During the 1770s Piranesi visited Pompeii on several occasions. Perhaps he intended to publish a large-scale illustrated volume about this ancient city, buried under four or five metres of ashes since Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD and until excavations began in 1748. 12 drawings from Pompeii A total of twelve Piranesi drawings showing various locations in Pompeii survive today. All of them are executed in the same manner. First, the scene was lightly traced by hand in pencil, then the main lines of the perspective structure were touched up using a pencil and ruler, and then everything - houses, sculptures, broken columns, inquisitive archaeologists and curious tourists - was given shape and mass by means of a reed pen and brownishblack ink. The drawing's motif The scene depicted here is located close to the Herculaneum gates and can still be found today. Everything is, however, rather more modest in appearance than this drawing would indicate. As the art historian Erik Fischer said: "Piranesi makes this scene sublime with the dark, concise force of his pen strokes. Tomb visitors bend over the resting places of the ancient dead. A learned nobleman, typical of the times, bids a dignified welcome to the shadowy figure emerging from the door to the right, as though hailing one of the Istacidi out from oblivion."

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.