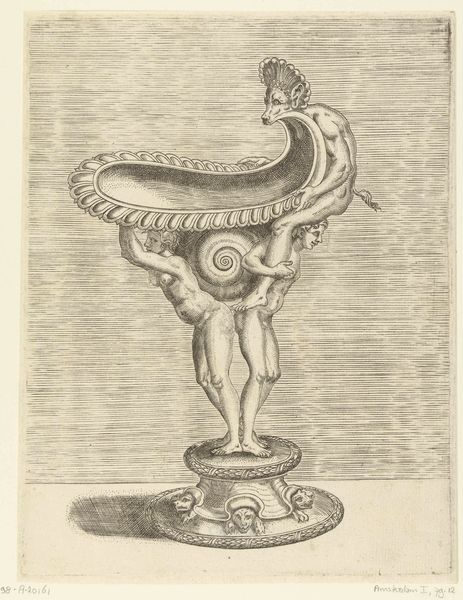

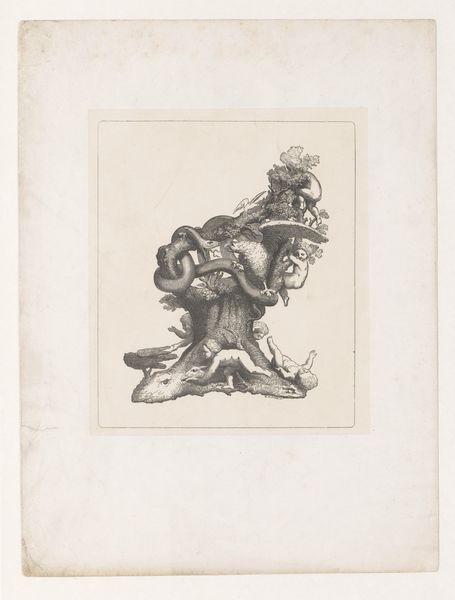

Schaal in de vorm van een schelp, gedragen door een sater die op een schilpad zit 1548

0:00

0:00

balthazarvandenbos

Rijksmuseum

print, etching, relief, engraving

# print

#

etching

#

greek-and-roman-art

#

relief

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

mythology

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 221 mm, width 166 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This intriguing 16th-century print is called "Schaal in de vorm van een schelp, gedragen door een sater die op een schilpad zit," created in 1548 by Balthazar van den Bos. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum, and what initially grabs you about this artwork? Editor: It's strikingly strange. I'm immediately struck by the unsettling blend of classical motifs twisted into this bizarre composition. A satyr perched on a turtle, supporting a giant seashell? It’s surreal. Curator: Mannerism loved this kind of elaborate fantasy, deliberately subverting High Renaissance ideals. Here we see a clear fascination with artifice. But what cultural baggage is in play with these characters, you think? Editor: The turtle is an obvious symbol of slow, steady progress and of the Earth itself. It feels almost burdened by the satyr on top. The satyr itself... what does his grimace signify while holding a seashell as big as himself? There is so much contained cultural and psychological weight embedded here. It is also fascinating how classical imagery is being reshaped here. Curator: The placement of a classical figure into modern compositions, something explored broadly with engravings. Van den Bos aimed at a learned audience acquainted with classical mythology, and there are definitely strong ties with ancient artworks throughout the museum as well as modern interpretations, and prints were a good medium to facilitate this dialog across time and locations. But it also says something about the society who enjoys them. Who gets to decode those embedded languages of the elite and powerful? Editor: Exactly. The trident, the figure riding in the shell, he looks as though he's out of his element; I would've anticipated Aphrodite. How does this strange arrangement change our expectations? Does it turn these power structures of masculinity, femininity, power and support upside down, to ask, again, about its culture in novel ways? Curator: Certainly! It makes the artwork itself like an arena for working out anxieties around inherited power structures, I imagine. The museum becomes a vital space, too, for preserving that dialogue. Editor: It is amazing that prints allows that discussion. Van den Bos is still relevant in the 21st century as in his 16th century. Curator: Precisely! We are so glad to provide this piece for future generations as well. Thank you for joining me today!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.