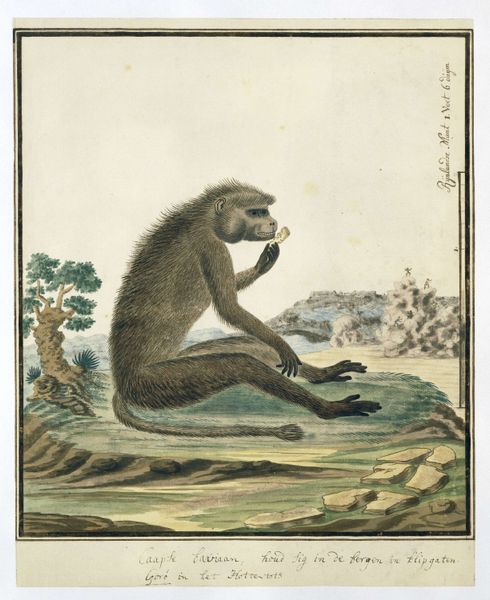

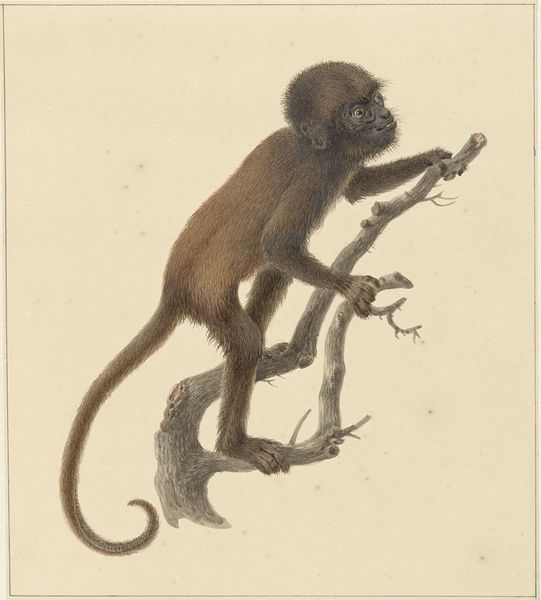

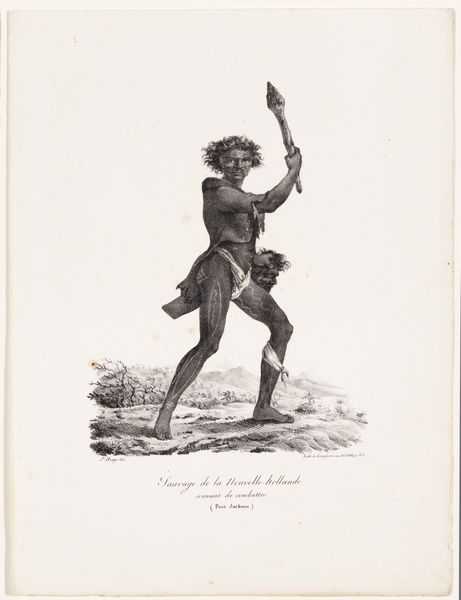

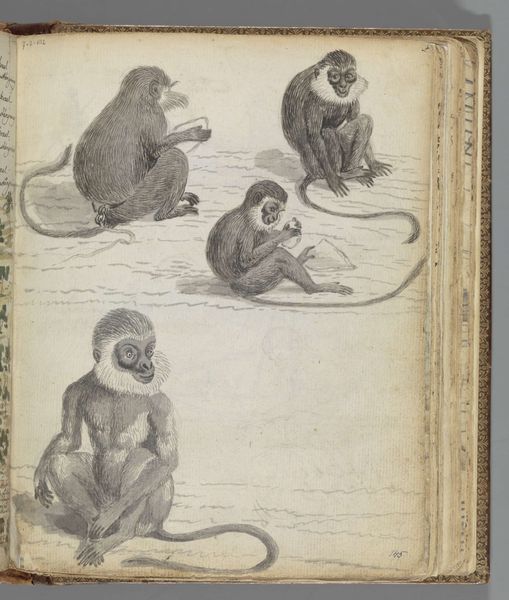

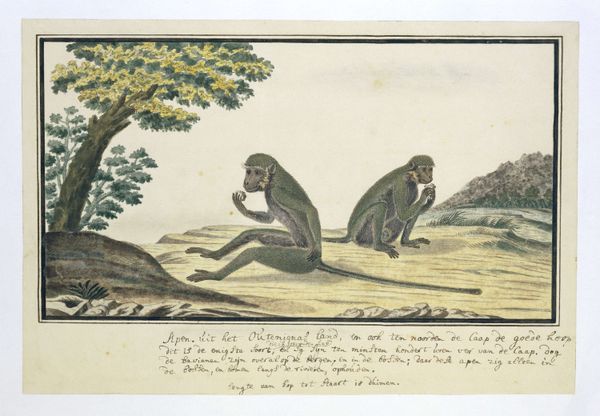

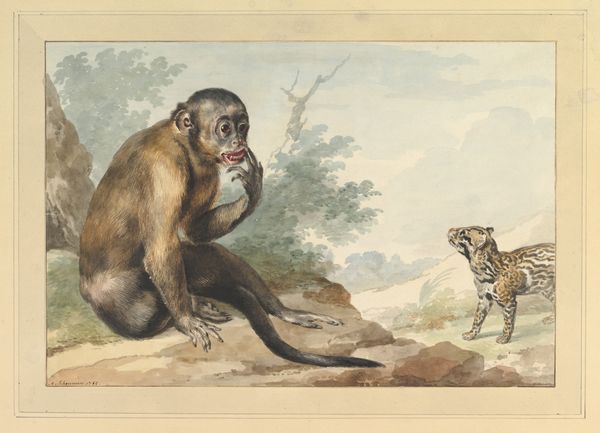

Illustration med aber: Chimpanse, orangutang og sort langarmet abe 1780 - 1836

0:00

0:00

painting, print, watercolor, engraving

#

water colours

#

animal

#

painting

# print

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

watercolour illustration

#

engraving

#

watercolor

Dimensions: 225 mm (height) x 140 mm (width) (plademaal)

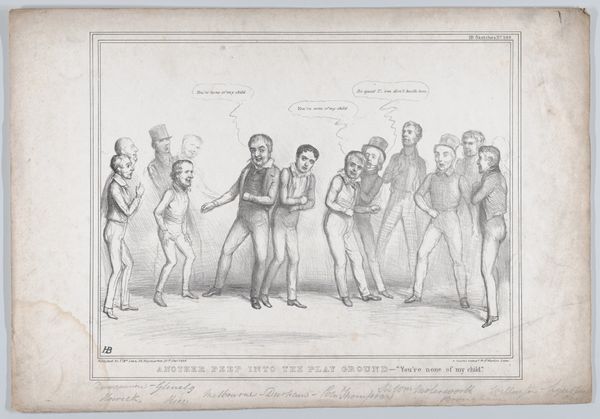

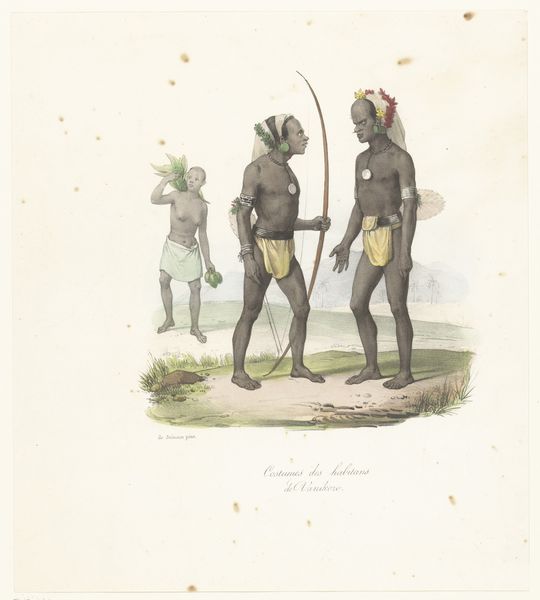

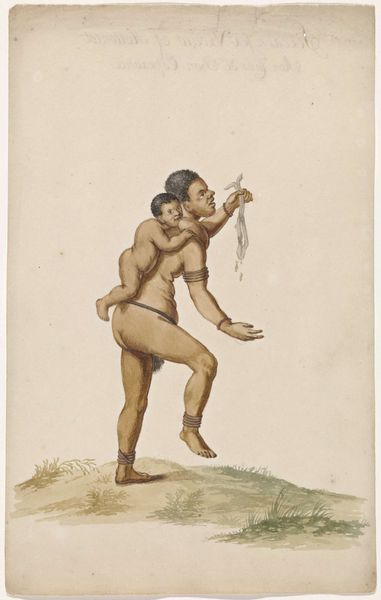

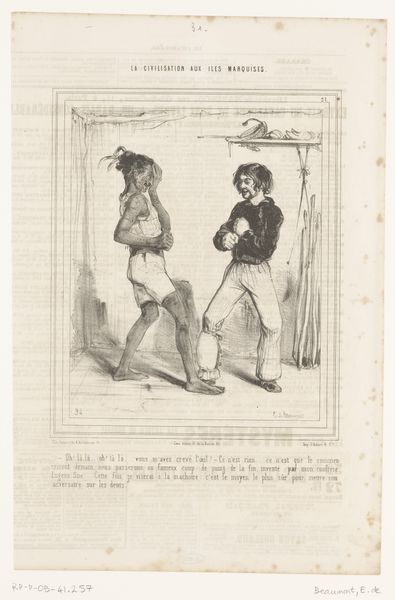

Curator: We're looking at Oluf Olufsen Bagge’s "Illustration med aber: Chimpanse, orangutang og sort langarmet abe," created sometime between 1780 and 1836. It's an engraving and watercolor. Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by the scale. The apes, rendered in these delicate watercolors, are contained on what seems to be a single sheet of paper, flattening them into almost scientific specimens rather than living creatures. Curator: Precisely! It's fascinating to consider how these prints circulated. As relatively affordable multiples, they brought images of the natural world into homes, shaping perceptions of both these creatures and the far-off lands they inhabited. We have to consider who the artist and engravers were, the processes by which they acquired images, and the societal values these images reflected back. Editor: And those societal values are undeniably problematic. I see the colonial gaze, right here. The reduction of these intelligent beings to mere illustrations reinforces a power dynamic – humans observing, classifying, and implicitly dominating the natural world, justifying exploitation and erasure in the name of scientific progress. Look how each is posed so statically, almost pinned. Curator: Indeed. And Bagge's process in creating this kind of "knowledge" involved not just rendering the image, but also replicating and distributing it via engraving. The means of production amplified the intended message, or, if we want to read it differently, made that message available to be contradicted. The labor itself, the etching and printing—that’s where real meaning lies, isn't it? The printmaking enabled, if not mass distribution, certainly increased viewership beyond the artist’s hand. Editor: It makes me consider the historical contexts – this work emerging during an era of intense exploration and colonial expansion, which provided both the subject matter and the demand for images like these. It speaks to how intertwined science, art, and colonialism truly were. These representations normalized an imbalance of power, contributing to the continued marginalization and dehumanization of both the depicted species and their native lands. Curator: Exactly! And the materials speak too. The paper stock itself indicates a level of commerce, trade networks established for both artistic and imperialistic means. The watercolors and the inks are commodities—consider where their source, manufacture and sale intersects with trade routes. It grounds the "art" in a wider system of material culture. Editor: Reflecting on this, it’s crucial we remember that artworks are not neutral. They actively participate in shaping our understanding of the world. By interrogating the historical, social, and political implications embedded in works like this, we become more critical viewers, better equipped to challenge problematic narratives and promote ethical modes of representation. Curator: Agreed. Looking at it through a materialist lens helps highlight that even simple works implicate large global industries and power structures, ones still relevant today. It’s not just a quaint depiction of monkeys. It represents exploitation in a number of interlocking social domains.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.