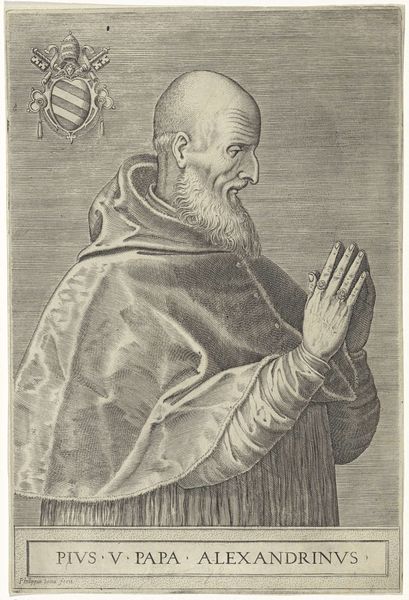

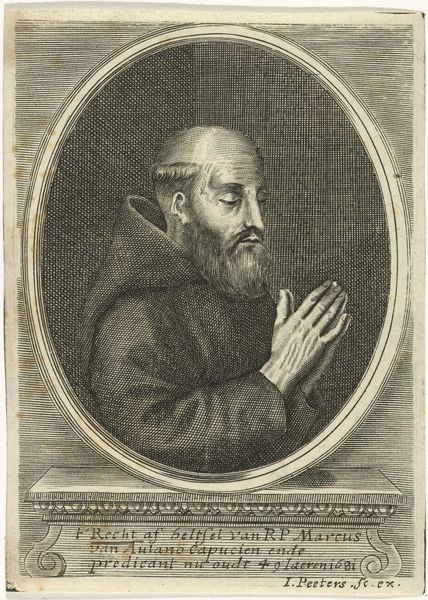

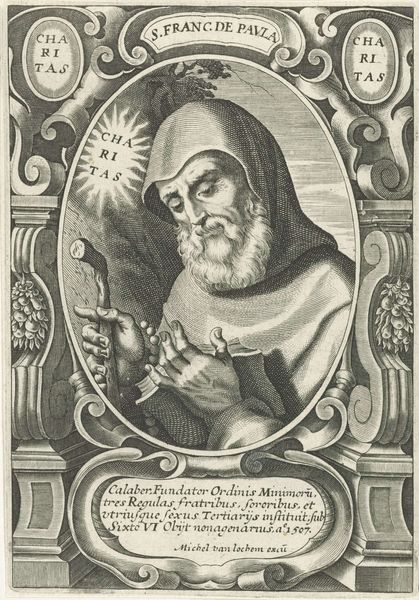

Portrait of Jan Pietersz. Sweelinck, Organist and Musician in Amsterdam 1624

drawing, print, engraving

portrait

drawing

dutch-golden-age

old engraving style

history-painting

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet (trimmed): 7 13/16 × 5 1/16 in. (19.8 × 12.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have a rather formal engraving, "Portrait of Jan Pietersz. Sweelinck, Organist and Musician in Amsterdam" by Jan Muller, created in 1624. I’m really struck by the precision of the lines, especially in the ruff and the hands. How would you approach this portrait? Curator: Well, let’s think about what went into creating this print. The act of engraving itself - the tools, the labor involved in meticulously carving lines into a copper plate - that’s where meaning truly begins. Consider the social status implied by having one's portrait made, but also reproduced and disseminated via printmaking. It becomes a tool for spreading his fame, right? Editor: Right, it amplifies his image, his brand, you might say. What’s interesting is that the artist, Jan Muller, clearly had a high level of skill but was still essentially functioning as a reproducer of images. Where does that put him in the art hierarchy of the time? Curator: Precisely! It’s easy to focus solely on Sweelinck, but let’s also focus on the economy of image production in 17th-century Amsterdam. The print is less about pure artistic genius and more about a commercial transaction. Who commissioned this print and for what purpose? These questions lead us to the complex social and economic relationships underpinning artistic creation at the time. And what about the distribution? How many copies were printed, and where did they circulate? The "aura" of a unique artwork dissipates under the weight of mechanical reproduction. Editor: So, you’re saying we shouldn’t just consider the subject of the portrait, or even the artist's skill, but also the means of production and consumption of this image as a commodity? Curator: Exactly. The paper, the ink, the press, the workshops – these are all essential components in understanding the work’s significance. Look at the lettering at the bottom: this informs us about Swelinck and positions Muller as his maker. Editor: That's fascinating, a totally different perspective on portraiture. Thanks! Curator: My pleasure. Looking at the labor embedded in its creation really brings this image to life, doesn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.