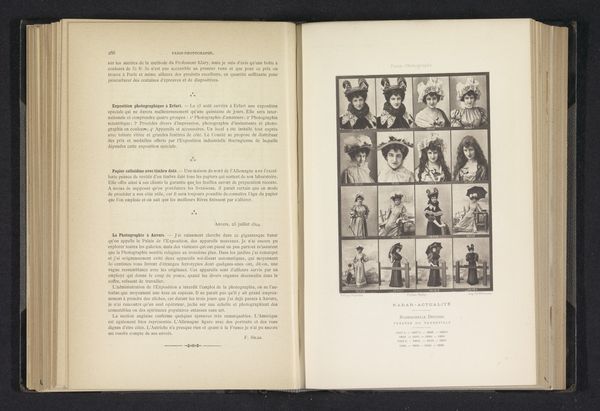

print, paper, photography

#

paper non-digital material

# print

#

paper

#

photography

#

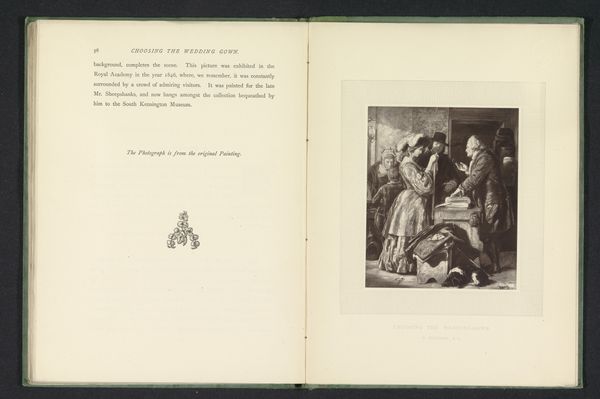

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 174 mm, width 105 mm

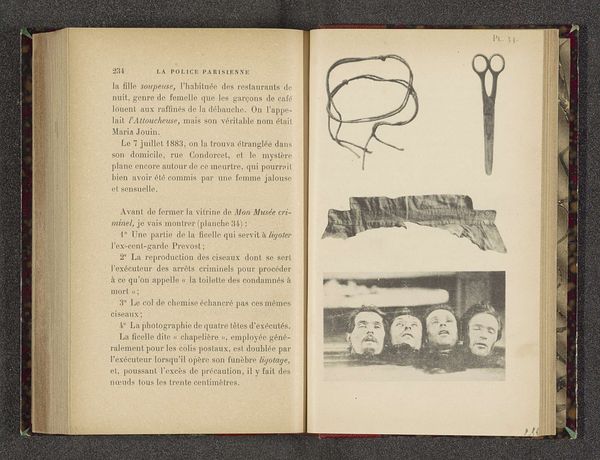

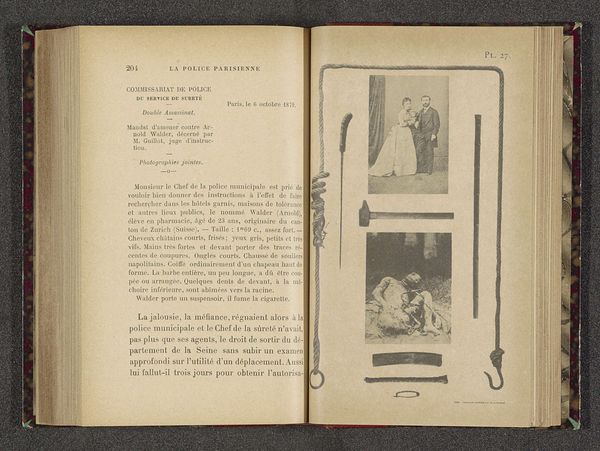

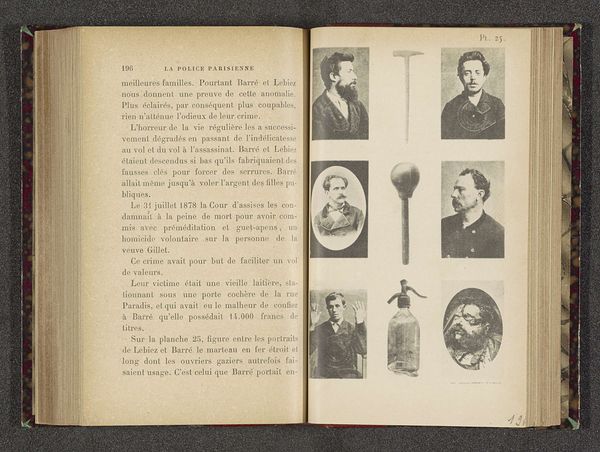

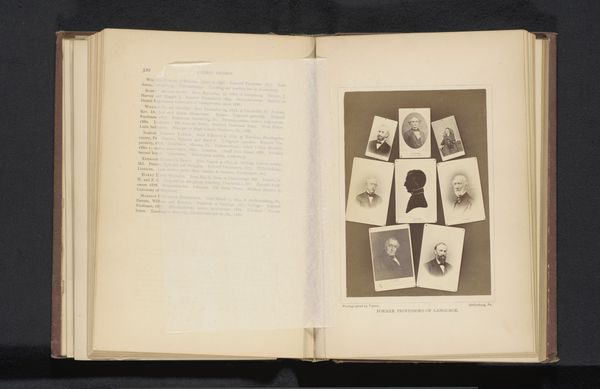

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

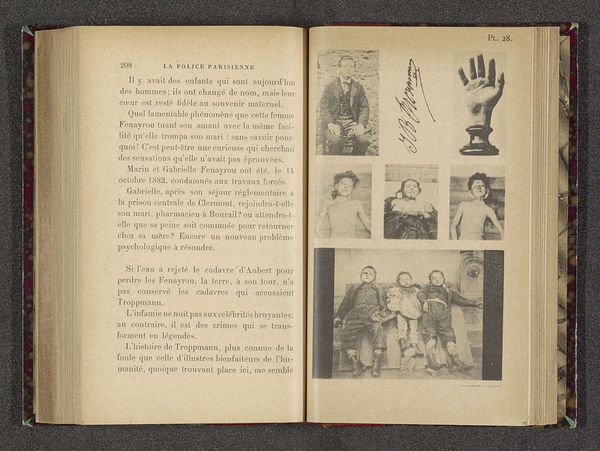

Curator: This rather grim page comes from an unattributed print titled "Zeven lijken, een pikhouwel en een portret van een onbekende man," dating to before 1890. Seven corpses, a pickaxe and a portrait of an unknown man! Quite a stark presentation. What's your first impression? Editor: My initial response is unsettling. The high-contrast photographs displayed alongside what looks like an ordinary tool immediately conjure a disturbing atmosphere, a real visual discordance between the banal and the brutal. Curator: Indeed. What’s striking from a historical viewpoint is how this image functions within the context of late 19th-century Paris and its relationship to crime. This is part of "La Police Parisienne." These post-mortem images, paired with a potential murder weapon, really speak to the fascination with criminality that permeated society at the time. This also shows the relationship between criminology, photography, and even nascent forms of visual media and social control. Editor: Absolutely. Thinking about its potential reception back then, I'm particularly struck by the implications surrounding anonymity and death, or rather how easily identities become absorbed within official record. And how often those systems fail already to give dignity to those whose images are recorded as part of their documentation. Curator: Furthermore, note how this compilation is being presented and consumed as almost a genre painting—historical events portrayed and mediated for the consumption of an audience interested in narratives around violence and transgression. We are forced to reflect upon issues related to representation and death, or to the treatment of the most marginalized, and how those relate to our ideas about politics and justice. Editor: Agreed. There's something profoundly unsettling in how the victims become, in essence, aestheticized. Curator: Yes, indeed, creating a certain distance. But on the other hand, one might argue that confronting such images, especially within the context of police archives and publications, might stimulate critical debate around justice, ethics, and social equity in their society, then and now. Thank you for shedding some light on how we consider this anonymous historical object in our own terms today. Editor: My pleasure. It's artworks like these that challenge us to confront uncomfortable truths about representation, social control, and human existence.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.