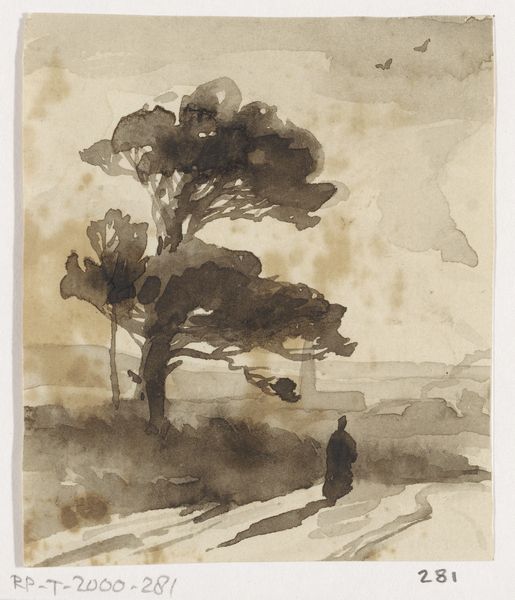

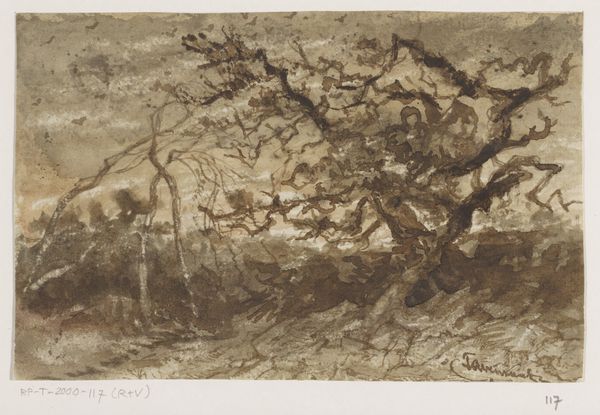

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 99 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This watercolor and pencil drawing, titled "Hunters and Dogs Under a Tree," comes to us from Johannes Tavenraat, dating it between 1840 and 1870. What are your first thoughts? Editor: Bleak, almost melancholy. The sepia tones lend a somber air. Everyone seems huddled together for comfort, the gnarled tree providing some sort of protection from that heavy sky. Curator: It's fascinating how Tavenraat captures that feeling with such a limited palette. Looking closer, we can interpret the hunting party as symbolic of social structures and hierarchies. Who gets to rest, and who remains on guard, perpetually vigilant? Even the dogs have a social structure. Editor: I'm intrigued by the choice of a lone tree as the focal point. Trees have held deep symbolic meaning across cultures – the tree of life, the axis mundi. The positioning here seems less about grand spiritual themes and more about tangible shelter, a communal gathering spot beneath its branches. Curator: And note the hunters' positioning – almost blending into the tree trunk, their identity blurred, perhaps commenting on the pressures and conformity demanded by 19th-century social roles. Their dependence on the landscape underscores nature’s powerful role in shaping human existence, offering both solace and imposing its own requirements for survival. Editor: The dogs themselves often symbolize loyalty and obedience but are also pack animals governed by their own instinctual pecking order. Perhaps Tavenraat uses them to further emphasize societal dynamics? Curator: Exactly! The interplay is rich. We also must consider the socio-economic implications. Hunting in this era speaks to land ownership, class privileges, and control over resources – critical topics when looking at broader colonial expansion during the Romantic era. Editor: So, in the end, it becomes more than just a bucolic scene. The image subtly layers ideas of social standing, resource accessibility, and human dependency within nature’s larger sphere of influence. Curator: Precisely. Tavenraat makes us reflect not only on an image of 19th-century hunting life, but a society under transformation grappling with industrialization, power structures, and environmental dependencies. Editor: It seems, for me, an allegory of vulnerability and reliance—themes resonating perhaps even more loudly in our own time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.