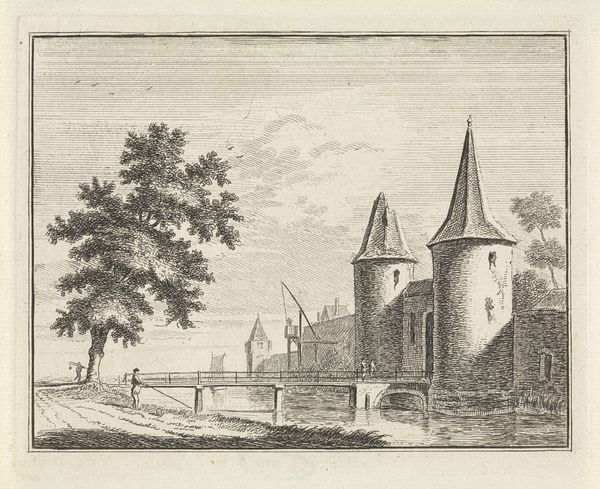

Dimensions: height 162 mm, width 142 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: We're looking at "Kasteel bij Wijk bij Duurstede," an etching and engraving made in 1765 by Hendrik van Maarseveen. It's a fairly simple landscape, dominated by the castle, but it has a somewhat melancholy feel, perhaps because of the ruined section next to the intact tower. What strikes you about this print? Curator: The melancholy you describe is interesting. Landscapes in this period were often commissioned or created as symbolic representations of power and order. To see a ruin included so prominently disrupts that ideal. I wonder about the patron—was this commissioned, or created independently for a public audience? Was the ruin perhaps a commentary on the shifting social or political landscape? The very act of portraying this, what does it imply? Editor: So the choice of subject is key here. The artist perhaps implying something about the powers that were? Curator: Precisely! Consider the audience too. Prints like these made art accessible, more democratic, in a way. This image would circulate; meanings would shift and change based on social context. Were people aware of decline of local aristocracies and land ownership at the time, and were beginning to be unsettled by them? Editor: That makes me think about the lone figure walking with his dog in the lower-left corner. He's a very small part of the overall composition. Curator: He is! But his presence transforms the scene. Is he an owner inspecting his property, or just a wanderer enjoying the view of something disappearing? Does the scale, dwarfed as he is, signal the fading power of humans against the ever-shifting tide of nature and time? Or does it, more optimistically, invite us to experience this landscape intimately, forging a personal connection with our historical past? Editor: I hadn't thought about how including him might be a commentary, too. Curator: And those are exactly the questions the image poses. This work highlights that prints served as sites for negotiating identity and historical consciousness during a period of enormous social change. Editor: This has given me a totally new way to look at 18th-century landscapes, so thanks. Curator: My pleasure, seeing art is just like opening a new book, isn’t it? There’s always a chance to reflect on humanity and society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.