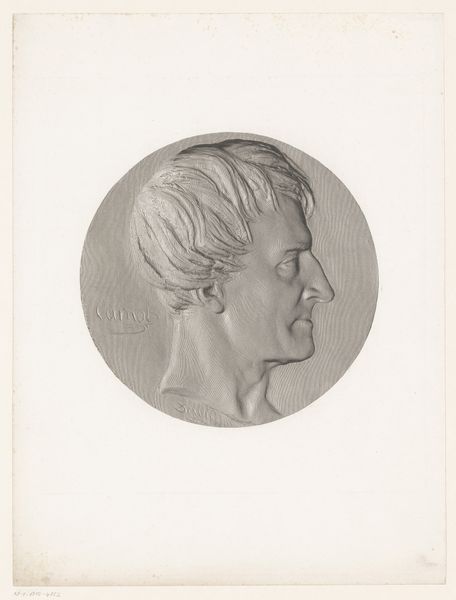

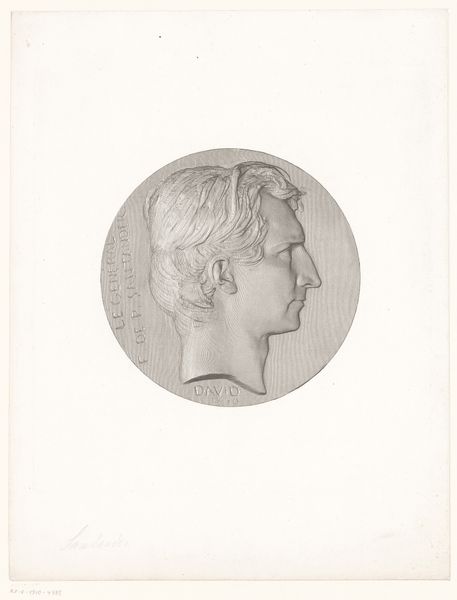

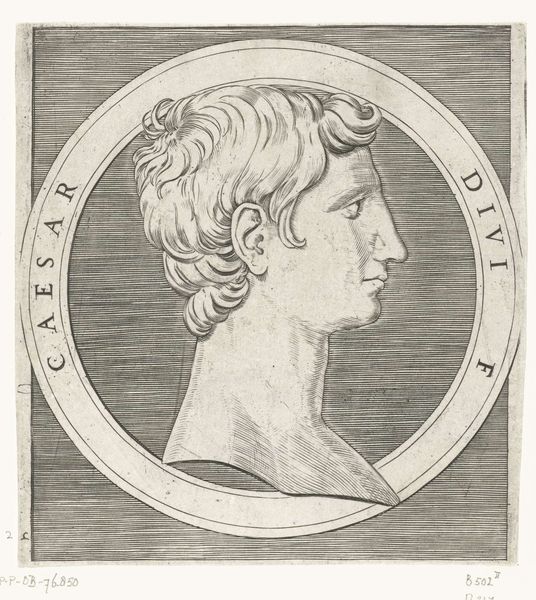

In honor of Prince Emmanuel Bibesco 19th century

0:00

0:00

metal, sculpture

#

portrait

#

medal

#

neoclacissism

#

portrait

#

metal

#

figuration

#

form

#

sculpture

#

men

#

line

#

decorative-art

#

portrait art

#

profile

Dimensions: 4 × 3 in. (10.2 × 7.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: What immediately strikes me is the rather austere beauty of this object, the resolute gaze and sharply delineated profile suggesting both classical ideals and individual character. Editor: Indeed. This is a bronze medal, titled "In Honor of Prince Emmanuel Bibesco," crafted by Jules-Clément Chaplain in the 19th century. Currently, it resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Curator: The profile is so commanding, so assured. You see these images on coins, rulers immortalized in sharp relief. But, more personally, don't you wonder what was he like? The prince looks quite severe, a seriousness emphasized by the material's cool permanence. Editor: That's precisely the interesting tension here. The classical mode was often used to elevate an individual into an almost timeless, idealized representation. Consider how portrait medals functioned within social and political circles. They could serve to broadcast power, celebrate alliances, and, more broadly, circulate particular messages about the subject's virtues and lineage. The inscriptions add to the cultural framework as well. Curator: True, but even within that carefully constructed persona, Chaplain manages to suggest an individual psychology. Note the precision in rendering the set of the jaw or the hint of a frown etched at the corner of his mouth. Even the Roman numerals indicating the year can feel laden with import. Do we know why Chaplain created it? Editor: Chaplain was a master medalist, often commissioned by prominent figures and institutions to commemorate significant events or honor individuals. Prince Bibesco, a member of a Romanian aristocratic family, was likely a patron. And although we are unsure, a coin of this time would not just have to be decorative, it could easily act as a symbolic pledge and sign of alliance. The portrait, embedded in the circular format, could represent protection for the wearer. Curator: Fascinating. The act of bestowing a portrait medal, then, becomes not only about aesthetic appreciation but also about negotiating power and solidifying social standing within these cultural parameters. I imagine the small scale makes the object portable. Like a calling card but weightier, something meant to be circulated and preserved. Editor: Exactly! Medals like this offer a glimpse into the visual rhetoric of the elite, showing us how identity was constructed and circulated through carefully crafted images in nineteenth century social circles. Curator: I am sure that Prince Bibesco was well aware of his role when it was made. How intriguing to consider its psychological weight now, across the span of so many decades.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.