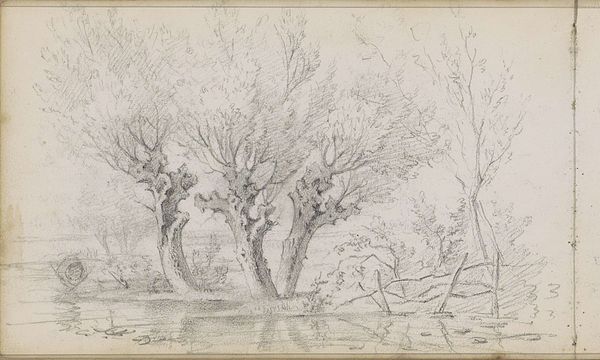

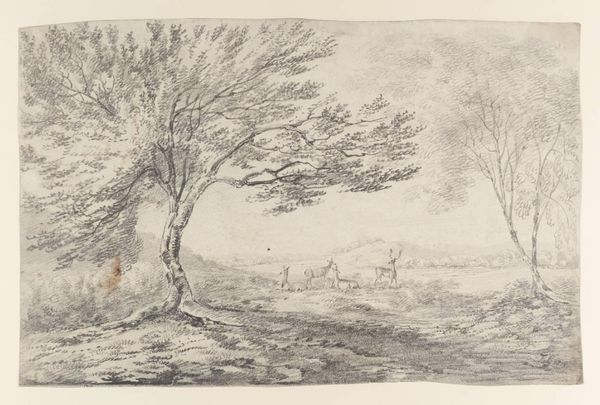

drawing, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

paper

#

pencil

#

realism

Dimensions: height 107 mm, width 175 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's turn our attention to this delicate drawing titled "Landschap met bomen," or "Landscape with Trees," created by Arnoldus Johannes Eymer sometime between 1813 and 1863. The medium is pencil on paper, and there’s a quiet realism to it. What strikes you first? Editor: An overwhelming feeling of melancholy washes over me. The trees, sketched with such simple lines, evoke a sense of solitude and impermanence. There's a starkness in the shading, a subtle memento mori present in the landscape. Curator: That somber tone certainly resonates, especially considering the social and political climate of the Netherlands during Eymer’s active years. Think about the period after the Napoleonic era and the ongoing struggle for national identity. Perhaps these simple trees represent something deeper. The rootedness of nature against human instability? Editor: Indeed. Trees have always held powerful symbolic weight – family trees, the Tree of Life. And here, the somewhat scraggly nature of these trees speaks of resilience, of survival. Are there specific species identifiable that might give clues? Curator: That’s a keen observation. While I couldn’t definitively pinpoint the species based on this sketch alone, it’s more crucial to recognize how the artist employed realism not as mere documentation, but as a form of silent protest. Nature, unburdened by human conflicts, offered a space of respite and silent resistance. This work asks if Romanticism has its place in sociopolitical activism, through depictions of familiar nature. Editor: I'm intrigued by the interplay of light and shadow here too. The light seems to be filtered, creating an almost dreamlike atmosphere. Could this also be seen as an exploration of inner emotional states projected onto the landscape? It reminds me a little of the psychology of Caspar David Friedrich and how, while we get surface-level "realism", the artist shows something completely unseen as well. Curator: Absolutely. We can even apply some post-structural theory by deconstructing traditional art and artist roles: the agency the landscape exerts on both the artist and the viewer transcends Eymer himself and transforms this seemingly simple drawing into something incredibly complex and historically relevant. Editor: Looking closely again, it's clear Eymer understood not only natural forms but also our longing for them. A quiet statement rendered in pencil. It definitely causes deep introspection, despite its apparent simplicity. Curator: It leaves us considering how landscapes are always more than what they appear to be and are often imbued with history, memory, and political undercurrents, regardless of their intended message.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.