Dimensions: 21 x 14 1/4 in. (53.34 x 36.2 cm) (sheet, margins cut)

Copyright: Public Domain

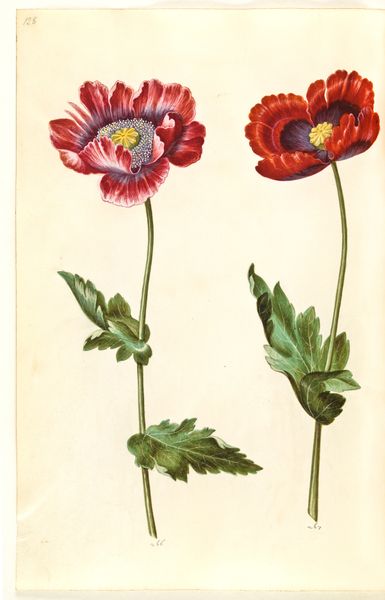

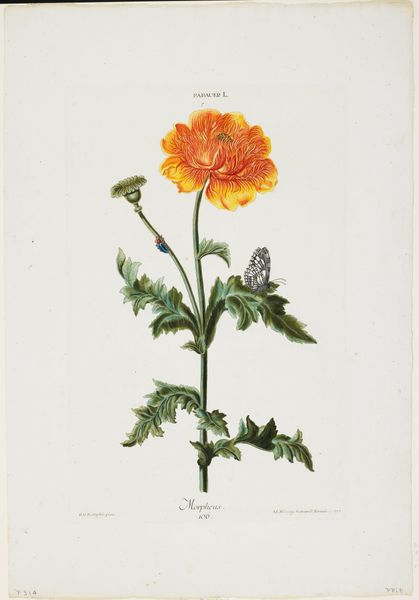

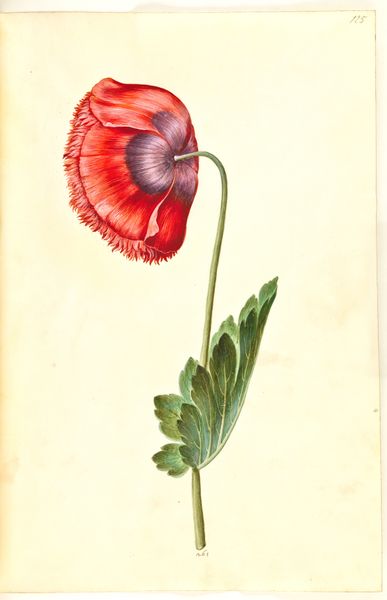

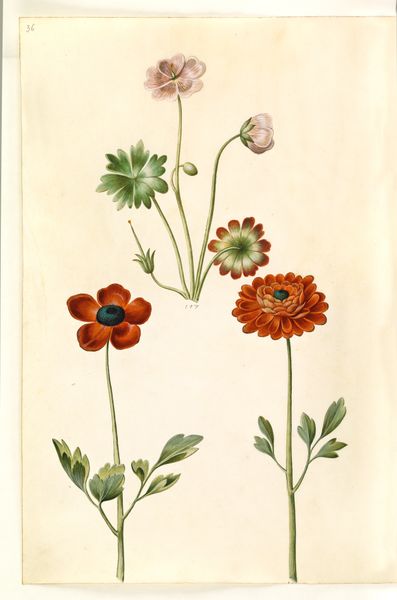

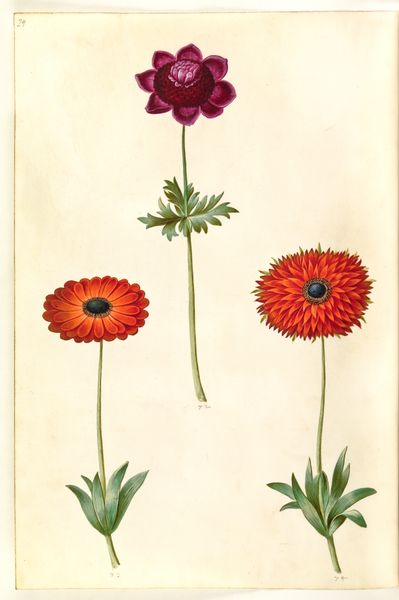

Curator: What a strikingly somber watercolor. Is that a study for mourning jewelry? Editor: We’re standing before “Study of Three Types of Poppies,” created in 1805. Currently housed at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, its artist remains unknown. I find myself drawn to the way it highlights not just beauty, but botanical structure. Curator: It’s curious how those blossoms droop, isn’t it? Each a distinct variety rendered in watercolour, though that deeply saturated palette, especially the near-black poppy, really speaks of a different intention than just observation. I see emblems of sleep, oblivion perhaps, woven into this floral arrangement. Editor: Precisely. Observe how the light plays across the paper. This meticulous approach suggests it served some didactic purpose within a craft or manufacturing context. These drawings were valuable resources to understand dyeing practices and properties derived from flora for example. Think of the practical applications beyond simple ornamentation. Curator: Ah, that throws a wrench in my hypothesis! Still, can't we consider the emotional undercurrent implied by poppies – dreams, peace, even death in some cultural memories? Might its creator have sought more than simply accurate botanical representation? Editor: I believe the choice of watercolour betrays how it may have operated outside the traditionally lauded medium of oils; paper allowed a speed and volume more easily used than costly canvas. By extension we ought also to ask how gender roles might shape the choices of technique by lesser known, sometimes overlooked talents working under artistic convention. Curator: I see your point. Maybe the symbolism I’m reading is an accidental, secondary result of this medium-specific process? Perhaps what intrigues me IS the result of someone grappling with those restrictions… or ignoring them completely! Editor: In truth, isn't it both? Considering context, access, methods; we gain richer ground for interpretation of not only *what* the art signifies, but what cultural and socio-economic mechanics shaped art’s very appearance as form! Curator: What a beautiful tension that creates - something both symbolic and so completely, intimately tied to the hands that brought it into being! Editor: Agreed. Every splotch and swirl speaks, so long as one remains ready to read its production too.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Botanical illustrators working in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries devoted themselves to the medicinal qualities of plants and sought to render plant structure and function as precisely as they could. Later, European explorers brought specimens back from exotic locales, and artists carefully reproduced them for an audience fascinated by new discoveries. By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, artists had shifted their emphasis from scientific illustration to the innate beauty of the plant or flower. The Minneapolis Institute of Arts is fortunate to possess an impressive collection of more than 2,000 botanical prints and drawings.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.