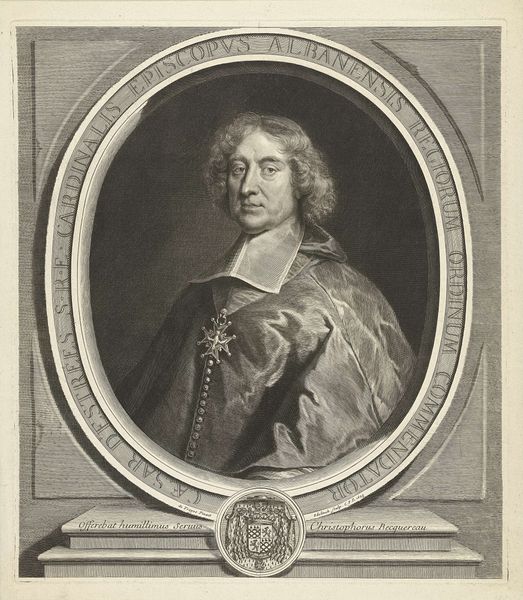

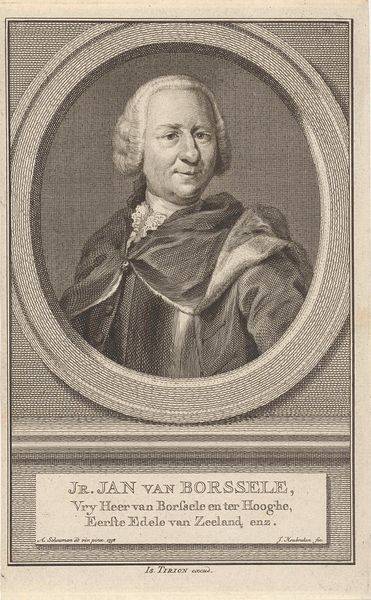

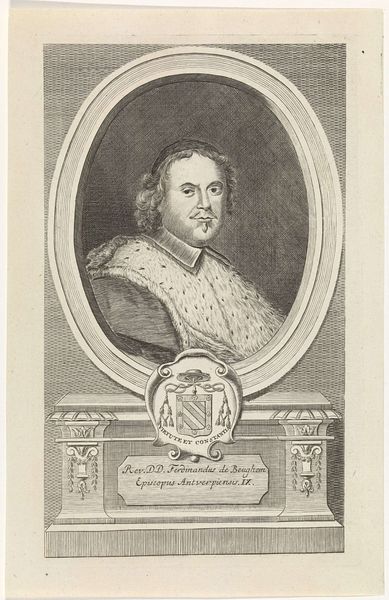

engraving

portrait

baroque

old engraving style

pencil drawing

line

history-painting

engraving

Dimensions: height 238 mm, width 189 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us, we see an engraving from around 1750, titled "Portret van Willem IV, prins van Oranje-Nassau," made by Pieter Tanjé. It's part of the Rijksmuseum's collection. Editor: It strikes me immediately as very… stately, I suppose is the word. The composition feels rather formal, with all the classic trappings of power. There's an almost theatrical quality to the portrait. Curator: Indeed. The work served the crucial role of solidifying Willem IV’s image and authority in a period marked by political transition in the Netherlands. Consider the cultural weight it held then as a representation of the revived Stadtholderate. The image would circulate through prints, reinforcing the Orangist cause. Editor: The use of specific symbols is fascinating. Look at the shield in the lower left corner bearing the heraldic lion—clearly evoking courage and strength but presented in this stylized, almost archaic manner. The architectural framing device, replete with foliage, gives Willem an air of timeless dignity. Curator: The visual rhetoric here aligns precisely with Baroque sensibilities prevalent at the time. Think of the broader political context—European courts strategically commissioned portraits to communicate power, legitimacy, and divine right. Tanjé, through this print, participates in this European theater of power. Editor: And the detail! Notice the baton, symbolizing command, positioned as an architectural support. A classical statement, yet subtly deployed to reinforce leadership, not through brute force but through established order. It shows how they connected to past models to authorize new power configurations. Curator: Absolutely, and let’s not ignore the economic factors at play. Consider the role of "Societ. Bibliopol. Rotterod. Excudit." marked beneath. These engravings, as disseminators of political ideology, were also products, sold to a public hungry for representations of power. This intersection of art and commerce is always important to observe. Editor: It gives you much to think about. Tanjé has left us an engraving that encapsulates the image crafting surrounding 18th century leaders. I appreciate observing all of the symbolism woven together here. Curator: I concur, studying it really underlines how seemingly straightforward portraits of figures can act as key social, political, and economic barometers of the period in which they're created.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.