drawing, dry-media, chalk

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

head

#

figuration

#

form

#

11_renaissance

#

dry-media

#

roman-mythology

#

pencil drawing

#

chalk

#

mythology

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

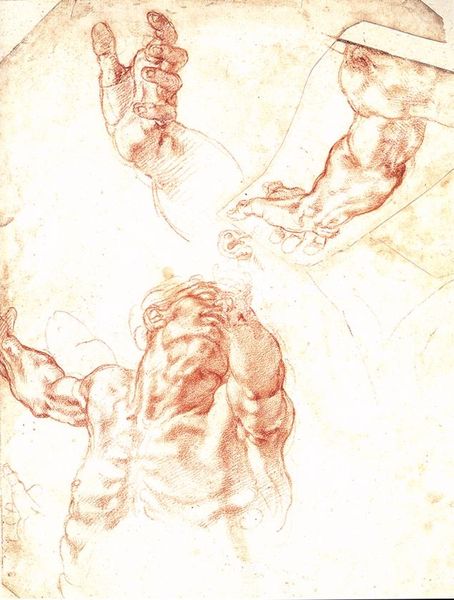

Dimensions: 28 x 21 cm

Copyright: Public domain

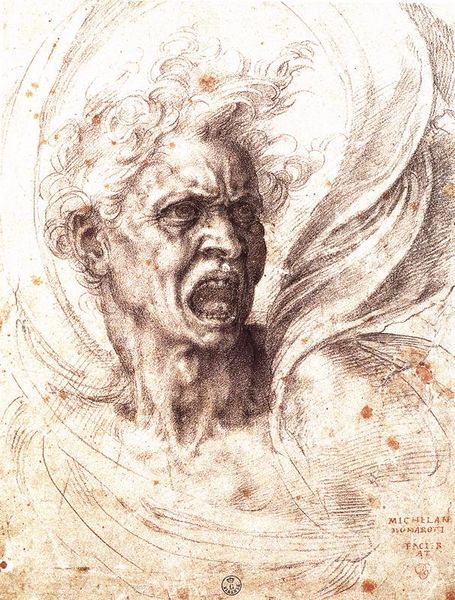

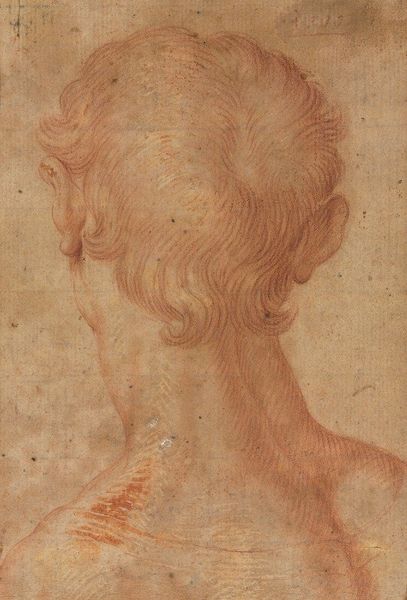

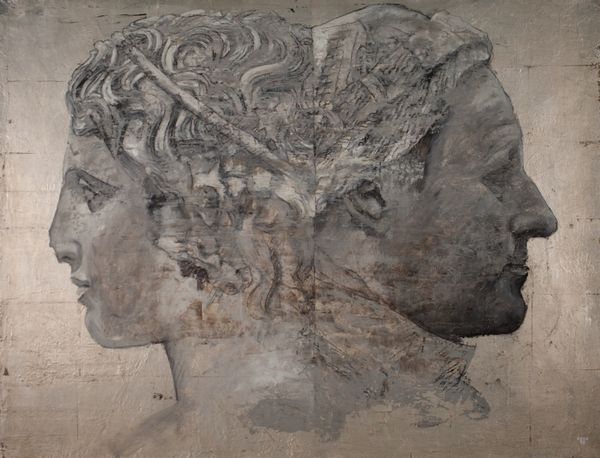

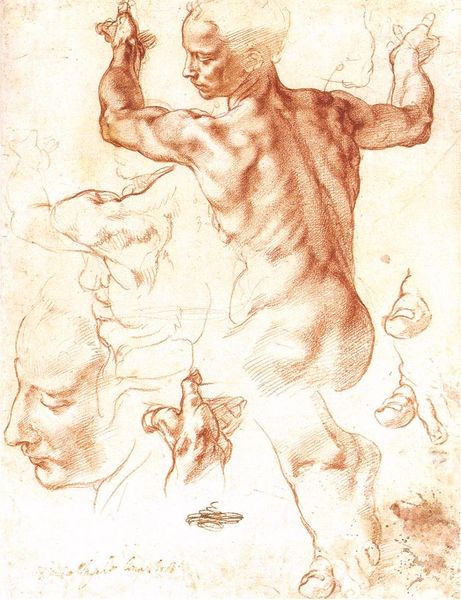

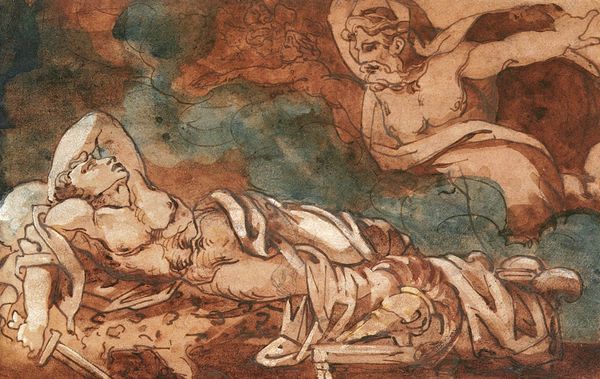

Curator: Here we have a drawing attributed to Michelangelo, entitled "Satyr's Head," housed here at the Louvre. Editor: There's something both delicate and intense about this sketch. The hatching marks almost look etched in, giving this mythological being a really earthy, tangible presence. Curator: Precisely. Consider the Renaissance revival of classical themes, here filtering through a study of form. We see in Michelangelo a renegotiation of mythological subjects within the prevailing humanist discourse of the era. Editor: And it is clearly a study. The materiality is really apparent - you can practically see the artist figuring it out, how light falls, the texture of the hair and skin... it’s all about process here. I imagine the red chalk medium was key, its pigment coming from the earth allowed for an immediate connection between artist, material, and subject. Curator: Absolutely. The "Satyr's Head" reflects the period's fixation with capturing not just physical likeness but inner character. The satyr, traditionally associated with Dionysian revelry, is portrayed here with a degree of introspective humanity. Do you find it surprising for the period? Editor: In contrast to idealised forms often presented at the time, it brings something quite different and complex. It certainly challenges simplistic binaries, it also reveals an investment in labour, and experimentation. How far was Michelangelo pushing these materials and what effects could be rendered in form and content? Curator: The emphasis on human form can certainly be linked to burgeoning Renaissance humanism, but through this lens, the work takes on the idea of social norms and how ancient forms and fables interact. How does one even read an artwork such as this one? I ask myself, am I making something up and projecting the concerns of today back into the 16th Century? Editor: Well, art history benefits from revisiting those dialogues, asking difficult questions... Otherwise, the past becomes silent. This gives agency and relevance. It breathes a new, vital relationship between now and then, you could say. Curator: True, it helps to think of the art world as a series of linked conversations—a series of palimpsests where stories and histories layer onto one another, building something vital and fresh. Editor: For sure! Looking closely at the material choices—and appreciating how those material choices intersect with cultural contexts and expectations, past and present—enables us to do so in complex and interesting ways.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.