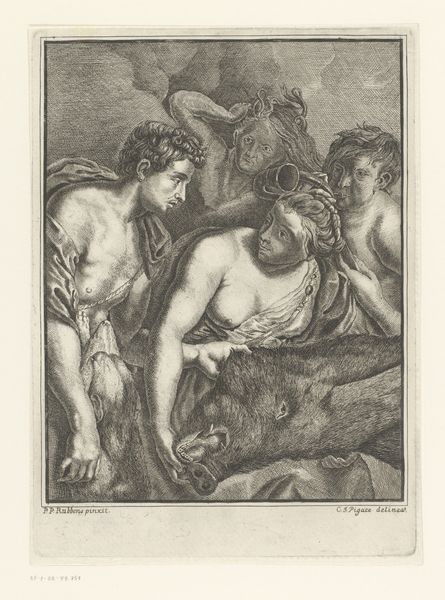

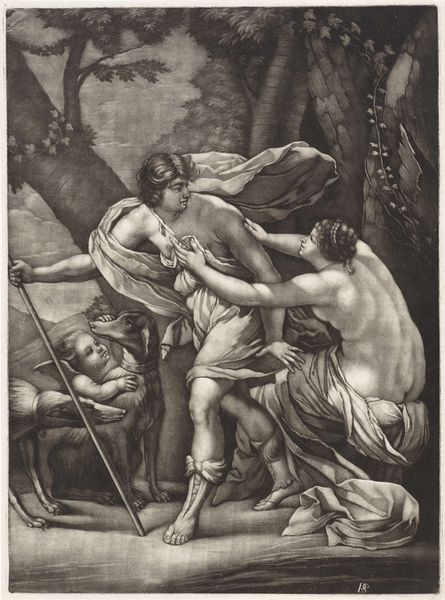

The three Graces and Mercury, after the painting in the Anticollegio, Palazzo Ducale, Venice 1518 - 1594

0:00

0:00

drawing

#

drawing

#

allegory

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

Dimensions: 204 mm (height) x 187 mm (width) (bladmaal)

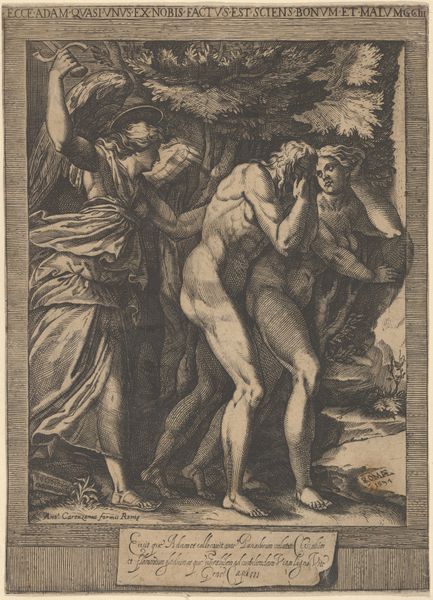

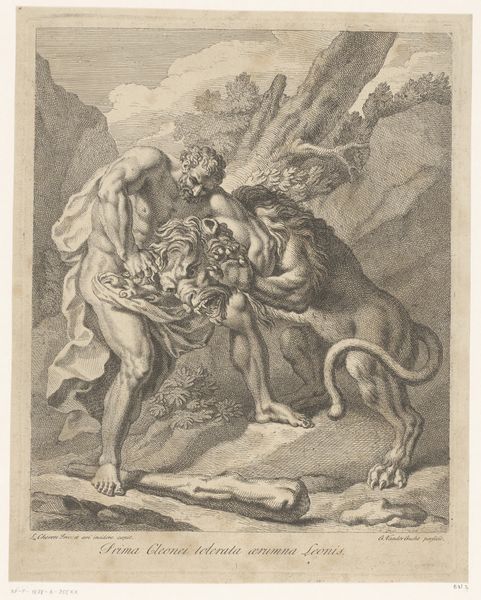

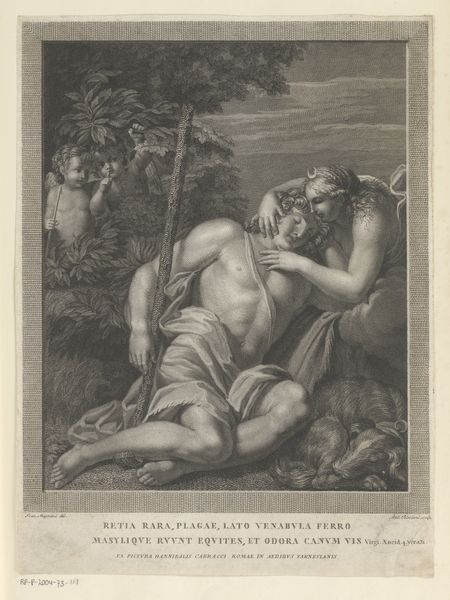

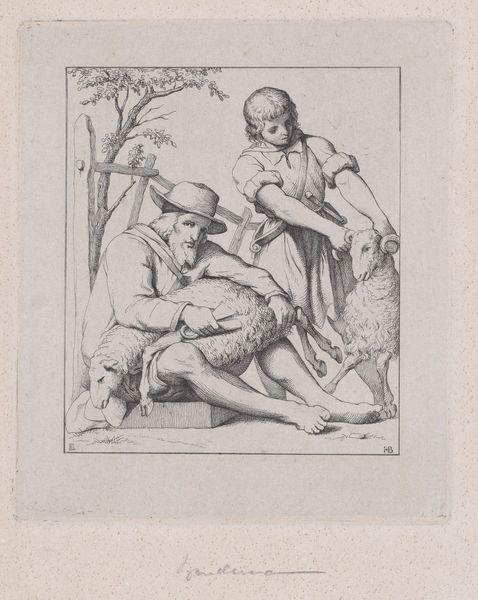

Curator: This drawing, made sometime between 1518 and 1594 by an anonymous artist, is titled "The Three Graces and Mercury, after the painting in the Anticollegio, Palazzo Ducale, Venice." It's currently held at the SMK, the National Gallery of Denmark. Editor: My initial reaction is one of classical repose. The soft grey wash creates a sense of serenity and timelessness. The figures are arranged almost as if on a frieze. Curator: Yes, that's quite deliberate. Considering this work as a drawing, one must consider its purpose in relation to production; this would most likely be a preparatory sketch or a copy for distribution. Editor: I'm struck by the implications of portraying these mythological figures as ideals of feminine beauty within the context of the Renaissance court. The Graces, often symbols of beauty, charm, and nature, alongside Mercury representing commerce and communication - what message was intended by displaying the female nude with themes of commerce and the nature of beauty? How much did ideas of humanism impact its design and consumption? Curator: Good questions. If we move beyond a strictly formal art historical approach, looking at materials gives clues. Note the skillful use of pen and wash; the anonymous artist has mimicked oil paint on paper. I’m most drawn to considering the means and modes of the paper support production in Venice during this time; these modes shaped artistic practice. Editor: It's interesting how even in this medium, designed to replicate a painting, the gaze seems complicit in a patriarchal view where beauty and virtue are visually consumed and aligned with power and social standing. One could read Mercury's inclusion as divine sanctioning of earthly pursuits. Curator: I agree, however, it is important to examine the artist’s specific technical approaches—the way light falls on the figures, for instance, and the precise manipulation of ink and paper to evoke a classical source. The artist here, regardless of gender, worked laboriously under highly controlled material constraints in this early reproductive system. The act of creating this work reflects certain conditions. Editor: So true. And by engaging with both these figures’ presentation within art historical power dynamics and exploring their artistic production process, we get a much richer picture, wouldn't you agree? Curator: Yes, indeed. There is a network of circumstances in play, reflecting broader Renaissance production economies as well as cultural values about gender and labor.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.